In 1996, Capitol Records bought 49% of Matador Records. Maybe the bigger label thought it would be investing in its own future if it got in early on the For Carnation or Bardo Pond or Silkworm. Probably not, though. Probably, Capitol wanted in on Liz Phair, and probably Capitol figured out that the best way to do it was to go through Phair's label. (A few years later, when Matador extricated itself from its Capitol deal, Phair was magically a part of the Capitol roster even though she'd never signed a deal with the label.)

Liz Phair was, after all, the same person who'd landed herself on the cover of Rolling Stone with an independently released debut album, winning critics polls and attaining verifiable cult-star status in the process. And the songs on Exile In Guyville and Whip-Smart were real songs, too. This wasn't a Guided By Voices situation where you could see the great pop songs buried under all the lo-fi murk. These were great songs, albeit eccentrically produced ones, that were right there, punching you in the face with their hooks. It shouldn't have been that hard to make her famous in that elusive non-cult way.

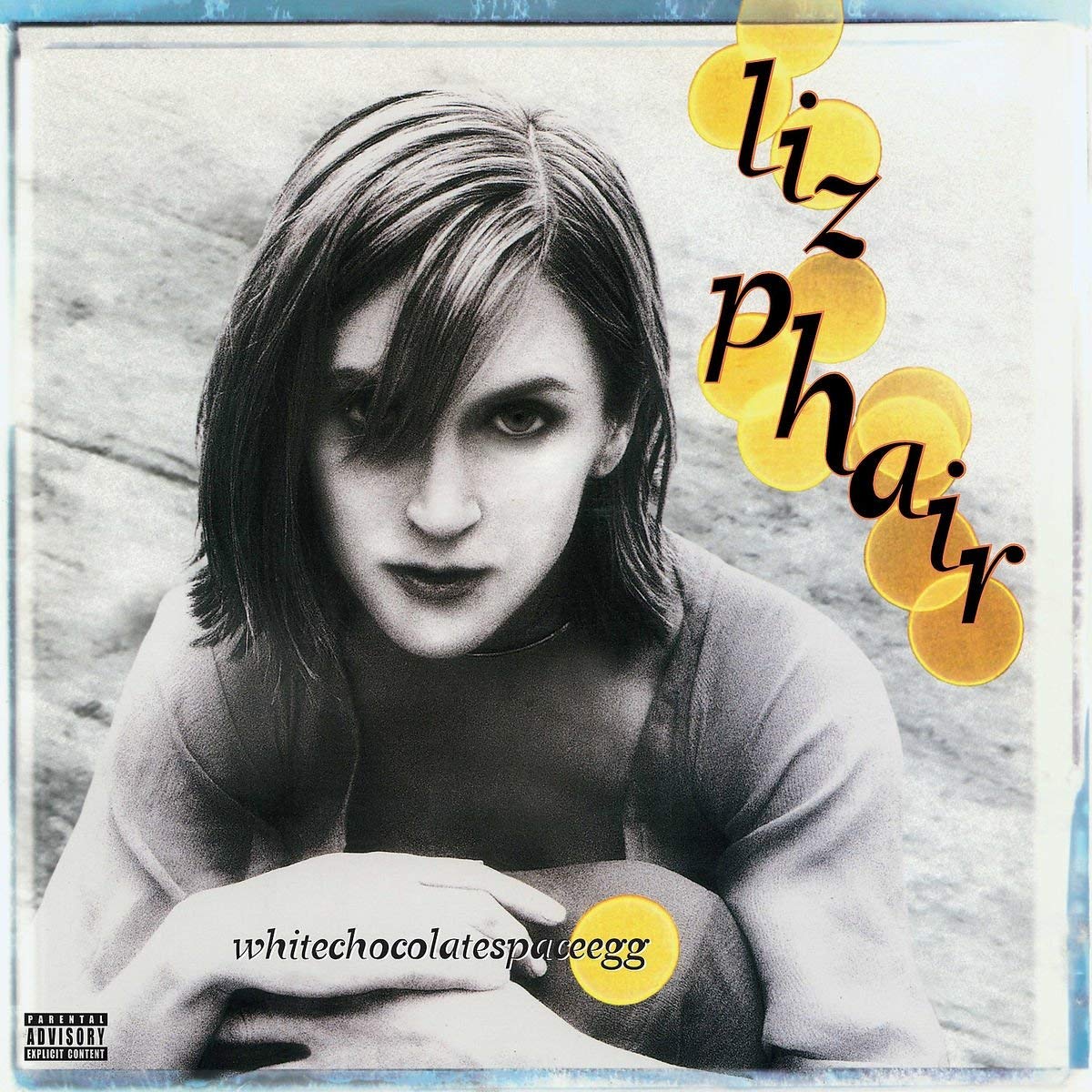

Whitechocolatespaceegg was the end result of those attempts -- a case study in what happens when the forces of the market began working on one of the great independent voices of the '90s. The album came out four years after Whip-Smart, Phair's tough and nasty sophomore album. She made it after working with a generous handful of producers, including R.E.M. buddy Scott Litt and her old Guyville collaborator Brad Wood. When she finished one version, her label sent her back to make something that might work as a single -- something that never would've happened to labelmates like Pavement or the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. As the album was coming out, Phair headed out with Lilith Fair, the festival package tour that mostly booked the radio-friendly folk-rock women who were inescapable on alt-rock radio. A year later, she opened for Alanis Morissette. She was playing the game.

Even if you don't know what came next, you can probably guess. Phair knew what was coming next, and she sang about it on the album itself. "Shitloads Of Money," the second-to-last song on the album, is a portentous look at what was about to happen with Phair's career: "It’s nice to be liked, but it’s better by far to get paid / I know that most of the friends that I have don’t really see it that way." A few years later, Phair would be posing for Xbox magazine ads and working with Avril Lavigne's production braintrust while Pitchfork lavished a 0.0 upon her perfectly decent radio-pop album.

Of course, plenty of bullshit would've been heading Phair's way even if she started making Jandek albums. The Phair of Whitechocolatespaceegg was simply not the Phair who had made Exile In Guyville. In the years between her second album and her third, Phair got married to a film editor who'd worked on her videos and had a son. (Whitechocolatespaceegg's kinda-unfortunate title may have been inspired by the shape and feel of her new baby's head.) Phair was no longer singing about wanting to be anyone's blowjob queen, and some people took that personally. (Witness the deep yawn of a Spin review that lamented the loss of Phair's "brainy-slut persona.") After two albums of critical hosannas, the response to Phair's third album was a slightly resentful shrug. And it's not like it was a sudden pop sensation, either; it ended up selling less than Exile or Whip-Smart.

Here's the thing, though: Everyone missed out. Because Whitechocolatespaceegg is a hell of an album. It's the end of a three-album run that I'd put up against anything from anyone, at any point in alt-rock history. The talk of Phair as a careerist was all a total canard. The songs are as hard and pointed and eloquent and honest as anything else that was out there in 1998, and the production's not exactly a whole lot cleaner. Phair wrote big and sticky hooks -- "Polyester Bride" was the sort of thing that can and should conquer your brain for entire afternoons at a time -- but she'd always been doing that. The album's arrangements are cluttered and smart and eccentric, full of sharp little touches that you only notice when you're paying close attention. The only real concessions to the sound of '98 were a few squiggly synths here and there, and Phair was better at using those than most of her contemporaries were.

Whitechocolatespaceegg might not hold up quite as well as Exile, but that's not a fair comparison for any album. A few Whitechocolate songs are a bit inert, but the best moments are charged with absolute electricity. Consider "Johnny Feelgood," the slick little blues reverie about the abusive man whose shithead qualities somehow make him more attractive ("Johnny makes me feel strangely good about myself"). Or the transcendent rockabilly goof "Baby Got Going," written from a gender-flipped perspective and charged with a very late-'90s interpretation of Johnny Cash's old train rhythm. Or the ecstatic way Phair breathes the line "positive T-cell regeneration" on "Ride." Or the exceedingly dry way that Phair, voicing the title character on "Big Tall Man," deadpans, "I can be a complicated communicator."

Phair didn't always write from her own perspective, but she always wrote with a vivid sort of insight; consider the way she inhabited the squabbling road-tripping couple on the Exile classic "Divorce Song." And there was always enough of her in there. Think about "What Makes You Happy," for instance. Phair's character tries to tell her mother than she's finally in a stable relationship, that she should stop worrying: "I’m sending you this photograph, I swear this one is gonna last / And all those other bastards were only practice." The mother's response -- "Listen here, young lady / All that matters is what makes you happy" -- kills me every time.

The narrator of that song knows, on some level, that she's doomed to further heartbreak. Maybe Phair knew that, too; she divorced her husband three years after the album came out. Young parenthood is a total shock to the system, and a lot of couples don't survive it. Maybe that's what Phair was singing about on a few parts of the album: "You and me are in way over our heads with this one, it’s hard to admit it," "Love is nothing, nothing, nothing like they say / You gotta get up and work the people everyday." Or maybe I'm reading in biographical details that just weren't there.

Either way, Whitechocolatespaceegg is a great fucking album, whether despite all the stressors that were working on Phair at the time or because of them. In the years that followed, those stressors wouldn't lead Phair to any more great albums. Her next two albums, both released from within the major-label system, permanently alienated vast swaths of her old audience and made Phair the target of performative trolling from whole new generations of internet critics. The only one she's released since then is the 2010 freaked-out quasi-mixtape Funstyle, an album that includes both rapping and Bollywood samples. She's been away for a while, but now she seems to be on the way back, touring with big alt-rock names and writing books and reportedly working on a new album with producer Ryan Adams. She has dealt with altogether too much bullshit, and it would be great if she could shake all of it off and record another album worthy of those first three. But even if that doesn't happen, Liz Phair has given us more than her share of great music. And if you've spent the past 20 years ignoring Whitechocolatespageegg, do yourself a favor and give it a shot.