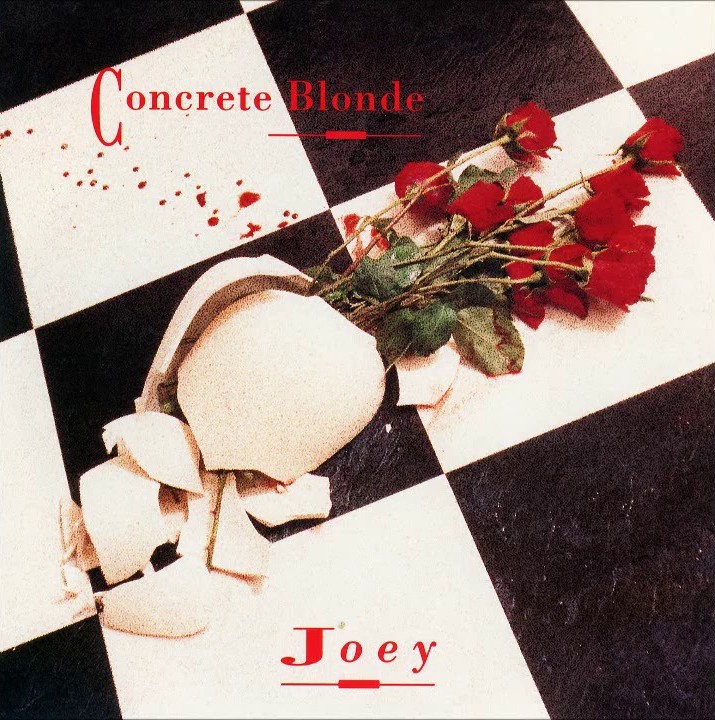

July 14, 1990

- STAYED AT #1:4 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

When your biggest hit doesn't sound anything like the rest of your music, how does that feel? This isn't a rhetorical question. I would really like to know. It's happened again and again throughout music history, and I'd imagine that the answer is different each time. Plenty of people are probably delighted to have any kind of hit at all, even if that hit is a stylistic and commercial fluke. Plenty of people probably came to hate their one hit very quickly. There must be some feeling of rejection involved -- the public loves this version of you but only this version. There must be pressure to recapture a success that refuses to be recaptured. It must be such a strange cauldron of excitement and disappointment and confusion.

Concrete Blonde aren't the most egregious example of that whole phenomenon, but the narrative definitely fits them. The group came out of the Los Angeles club scene in the moment after punk rock but before glam-metal, when the town hadn't really landed on a dominant sound. They were tough and scratchy and dark, and they didn't have an obvious lane. They weren't quite goth, but they weren't quite hard rock, either. They were respected, but they weren't super-popular, and they never really became a critical sensation. They were simply part of the landscape of modern rock radio when that landscape first took shape. And then "Joey" happened.

If you were an informed listener who heard "Joey" on the radio for the first time in 1990, you probably could've guessed that it was a Concrete Blonde song. Bandleader Johnette Napolitano has a raw, husky, ferocious voice that doesn't really sound like anyone else. She brings a certain intensity to everything that she does, and that intensity is evident on "Joey," a song that means a whole lot to her. Other than that, though, "Joey" has little in common with the growl-stomp night-creature music that Concrete Blonde mostly made. Instead, it sounds like a Stevie Nicks power ballad, a play for VH1 respectability.

Bloodletting, Concrete Blonde's third album, is an ambitious work that sounds a whole lot bigger and more textured than Concrete Blonde's first two. But even in the context of Bloodletting, "Joey" stands out. It sounds bigger, softer, more sensitive. It was an anomaly on modern rock radio, which is probably why it crossed over and became Concrete Blonde's only proper hit. After "Joey," Concrete Blonde made a few other songs that did well on alternative radio, but they were still primarily known as the band who made "Joey." That must feel weird.

It feels disrespectful to call Concrete Blonde a one-hit wonder, since the band's legacy looms a lot larger than the one song. From a zoomed-out perspective, though, it's hard to argue that the label doesn't fit the band. Concrete Blonde had one Hot 100 hit, and that hit was "Joey." Everything else that they ever did was firmly in the cult-favorite zone. With that in mind, it's a little wild to learn that "Joey" is also a song about a one-hit wonder. Johnette Napolitano wrote "Joey" about the difficulty of being in love with a self-destructive alcoholic, and the person who she had in mind wasn't really named Joey. Instead, it was Marc Moreland, guitarist for Wall Of Voodoo, the band who made "Mexican Radio."

Wall Of Voodoo came out of Acme Soundtracks, the failed film-score business that frontman Stan Ridgway tried to launch. Ridgway's office was across the street from the Masque, a hugely important early LA punk club, and he became friendly with Marc Moreland, then the guitarist in a band called the Skulls. Ridgway and Moreland started making music together in the late '70s, and their debut EP came out in 1980. Two years later, the band's twitchy-quirky jam "Mexican Radio" got a lot of early-MTV play, and it took off enough to reach #58 on the Hot 100. Wall Of Voodoo stuck around until 1988, but they never made another hit, at least in the US. In Australia, Wall Of Voodoo landed on the charts a few more times, and Johnette Napolitano met Marc Moreland when Concrete Blonde opened an Australian tour for Wall Of Voodoo.

When "Mexican Radio" took off, Concrete Blonde were just starting to become a band. Johnette Napolitano grew up in Los Angeles, where her father worked as a pool cleaner for movie stars. Napolitano had some weird intersections with celebrity culture. In a 1990 Spin profile, she says that Bela Lugosi used to babysit her and that her aunt was once engaged to the Monkees' Mickey Dolenz. Napolitano probably hung out at the Masque, and she started making music with guitarist James Mankey in 1982.

James Mankey is five years older than Napolitano. In the early '70s, Mankey and his brother Earle played on the first couple of records from Sparks, the art-rock band led by brothers Ron and Russell Mael. But when the Mael brothers moved Sparks to the UK, the Mankey brothers stayed put in California. Earle Mankey became a pretty successful record producer, but James didn't get anything going until he and Johnette Napolitano formed a band called Dreamers. Mankey played guitar, and Napolitano sang and played bass. She didn't know how to play bass at first, but they couldn't find a steady bassist, so she took it on herself.

Dreamers had one song, a spiky goth-punk jam called "Heart Attack," on the 1982 compilation The D.I.Y. Album. (Black Flag's "Six Pack" was on the same comp.) Then Dreamers found a drummer named Michael Murphy, changed their name to Dream 6, and released a self-titled independent EP in 1983. It sounds a bit like what might've happened if Pat Benatar led Siouxsie And The Banshees. I like it. That EP got the band a deal with IRS Records, the label that pretty much defined the sound of American alternative rock in the '80s. (Wall Of Voodoo were an IRS band, too.) Michael Stipe, leader of IRS flagship act R.E.M., suggested that Dream 6 change their name to Concrete Blonde. Even though Johnette Napolitano is not blonde, the band agreed.

The newly rechristened Concrete Blonde found a new drummer named Harry Rushakoff, and released their self-titled debut album in 1986. The band co-produced the LP with James Mankey's brother Earle, who also did the Dream 6 EP, and Johnette Napolitano wrote most of the songs herself, as she'd do through most of Concrete Blonde's run. Concrete Blonde is a strange little curio. There's plenty of trashy LA punk snarl and a little country twang on the record. But you can also hear Napolitano trying to sound like the Pretenders' Chrissie Hynde, and there's really just no way that anyone else can credibly pull that off.

The first Concrete Blonde album didn't make much noise, though some of its songs appeared on the soundtrack of the truly awesome 1987 alien-serial-killer flick The Hidden. Apparently, there are some Concrete Blonde tracks in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, as well, though I've never seen that one. That's where Concrete Blonde were after one album: A band whose songs turn up in soundtracks to fun '80s B-movies. That changed when the band's sophomore album, 1989's Free, started off with "God Is A Bullet," a genuine college-radio hit that reached #15 on the Modern Rock chart.

"God Is A Bullet" fucking rocks. Johnette Napolitano wrote the song as a sincere statement against American gun violence, but the song stomps and sneers with too much cartoony Crampsian energy to resonate as a protest. Instead, it comes off as rip-snort quasi-glam, and whenever I heard in on the radio as a kid, I thought it was the most badass shit in the world. Last year, Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, Maika Monroe, and Jamie Foxx starred in God Is A Bullet, a Satanic-cult revenge movie that went straight to Redbox. So I guess you could say that Concrete Blonde went from appearing on B-movie soundtracks to, decades later, inspiring the titles of B-movies. That's a pretty good trajectory!

"God Is A Bullet" was the only track from Free that really popped. Concrete Blonde were in some kind of weird contract situation when they got to work on their 1990 follow-up Bloodletting. The band temporarily moved to the UK and went to work with Chris Tsangarides, a veteran producer who'd mostly worked with metal bands like Anvil and Tygers Of Pan Tang. Johnette Napolitano was a big Thin Lizzy fan, and Concrete Blonde covered that band's song "It's Only Money" on Free. Tsangarides worked on Thin Lizzy's last couple of albums, so that's why Concrete Blonde wanted to work with him. But Tsangarides had also worked with gothier bands like Killing Joke and Lords Of The New Church, and he was able to help Concrete Blonde conjure a nicely spooky atmosphere on Bloodletting.

Concrete Blonde went through some lineup shifts before recording Bloodletting. On Free, the band took on a new bass player, and Johnette Napolitano focused entirely on vocals. On Bloodletting, they dropped the bassist and went back to a three-piece lineup. Drummer Harry Rushakoff missed the flight to London, and when the band played a show over there, they picked their next drummer out of the audience. Paul Thompson had played for British glam-rock heroes Roxy Music all the way through the early '80s, and he stepped in to become Concrete Blonde's drummer. (Rushakoff returned to Concrete Blonde in 1992, and Thompson is back in Roxy Music's touring lineup these days.) Still, Concrete Blonde were very much Napolitano's band, and I'm not sure her supporting cast ever mattered that much to the final product.

Bloodletting is a great record. It's searching and contemplative, but it's also vicious. Johnette Napolitano is hard and commanding, and the music has some of the same windswept desolation as the Cure's Disintegration, but it also rocks hard when it wants. "Bloodletting (The Vampire Song)," the album's opening track and lead single, didn't make the Modern Rock chart, but it's some supremely fun cape-swooshing silliness that would sound perfectly at home on any Halloween playlist. Most of the album is more serious than that, but most of it fits that vibe. "Joey," on the other hand, is something else.

"Joey" didn't start off with lyrics. Instead, the band recorded a rough instrumental demo, with Napolitano just voicing nonsense sounds. She knew what she wanted to sing about, but she had a hard time writing it. She'd been dating Wall Of Voodoo's Marc Moreland, who had serious alcohol problems that would eventually kill him. The subject was painful for Napolitano, and she didn't want to put her feelings into words until the last minute. (She later said that she called the song "Joey" instead of "Marc" because the real guy's name "doesn't quite have the same ring to it.") Napolitano put off writing her "Joey" lyrics to the point where the song was the last that she recorded for Bloodletting. Ultimately, she wrote those lyrics in a cab while she was on her way to the studio.

I didn't know the story of the "Joey" lyrics until I researched it for this piece, but Napolitano's story makes perfect sense. The "Joey" lyrics aren't remotely sophisticated, but Napolitano belts them out with huge storm-clouds-gathering emotion. There's a bit of tension between the elementary lyrics and the wild-eyed, feverish delivery. Maybe Napolitano could've worked on those lyrics a little more, but then maybe she would've lost her nerve. Maybe the song needs that first-draft immediacy.

Still, "Joey" does communicate the feeling of being hopelessly stuck on somebody who's in the middle of a self-destructive spiral. You can tell that Napolitano is protective of this guy. She's probably gotten sick of his bullshit. They've probably had some terrible fights. More than anything, though, she's worried about him, and she wants him to know that she supports him: "If it's love you're looking for, then I can give a little more/ And if you're somewhere drunk and passed out on the floor/ Oh, Joey, I'm not angry anymore."

There's no distance to "Joey." It's not a song written after the end of a relationship. It's from someone who's right in there, dealing with the chaos, not sure how to feel yet. It's less of a love song, more of a fear song. You mostly hear that in Johnette Napolitano's voice, which is tough and smoky until the moment when you hear her crack. Some of the music reflects that desperation; the opening "Be My Baby" drum-hits are practically a cheat code for conveying vulnerability in rock music. But too much of the production and instrumentation on "Joey" is pedestrian late-'80s rocker shit. The guitar solo is closer to Poison than to the Cure. I wonder how much of that was just an inescapable part of Concrete Blonde's DNA. Maybe you just couldn't play the late-'80s LA club circuit without soaking up some of that glam-metal pomp. I hear some of the same thing in Jane's Addiction and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, a couple of bands who will soon appear in this column. The song is caught between rawness and polish, and it never quite coheres.

The "Joey" video went for a fully literal interpretation -- Concrete Blonde playing in an empty bar while some guy drinks whiskey. It all seems pretty low-budget, but it didn't stop the song from connecting. "Joey" was huge on alternative radio, and it crossed over to mainstream rock and then to pop and even adult contemporary. The song became a top-five hit in Australia and Canada, and it peaked at #19 on the Hot 100. On a 1991 episode of Beverly Hills 90210, Brandon dated a young single mother with a kid named Joey, so "Joey" naturally soundtracked one of their moments together. Bloodletting went gold even though the album didn't have any other hits -- or, for that matter, any other songs that sounded anything like "Joey."

Probably through awkward timing, Concrete Blonde's "Joey" follow-up was a cover of Leonard Cohen's "Everybody Knows," recorded for the soundtrack of Pump Up The Volume, the 1990 teensploitation flick where Christian Slater plays a rebellious high-school pirate-radio DJ. I haven't seen that movie since I was a kid, but I loved it then. The "Everybody Knows" cover has Johnette Napolitano making the mystifying and disastrous decision to kinda-sorta rap Cohen's lyrics, and it peaked at #20 on the Modern Rock chart. "Caroline," a really good late Bloodletting single, peaked at #23, and that was it for that album.

The grunge era was not kind to Concrete Blonde. The band went back to Chris Tsangarides for the 1992 follow-up album Walking In London. Its lead single "Ghost Of A Texas Ladies' Man" is a whole lot more fun than "Joey." It went to #2 on the Modern Rock chart, but it didn't bother the mainstream. (It's an 8.) The quasi-ballad "Someday?," another Walking In London single, made it to #8. (It's a 6.) "Heal It Up," the lead single from Concrete Blonde's 1993 album Mexican Moon, couldn't get past #16. Neither of those albums sold anywhere near as well as Bloodletting, and Concrete Blonde broke up in 1994.

After Concrete Blonde, Johnette Napolitano and Marc Moreland covered the Carpenters' "Hurting Each Other" for the tribute compilation If I Were A Carpenter and then formed a new band called Pretty And Twisted. They released one 1995 album before splitting up, and Moreland died of liver failure in 2002. He was 44. In 1996, the non-David Byrne members of the Talking Heads, a band that'll eventually appear in this column, formed a band that was just called the Heads and released an album called No Talking, Just Head. (I still can't believe this happened.) Napolitano co-wrote and sang on the album's single "Damage I've Done," and she toured with the Heads. But Byrne sued, and the Heads ended.

In 1997, Napolitano and the LA band Los Illegals recorded an album called Concrete Blonde Y Los Illegals. In 2002, she got back together with the classic Concrete Blonde lineup, and they released another album called Group Therapy, followed by Mojave in 2004. They haven't released anything since, and they haven't played any live shows since 2012. Napolitano released a few solo albums, moved out to Joshua Tree, and became a tattoo artist. Alt-rock heads of a certain age still speak of Concrete Blonde with reverence. For everyone else, there's "Joey" -- not a great representation of who Concrete Blonde were, but also not a bad song.

GRADE: 6/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the "Joey" cover that Illinois duo Local H released on their 2010 covers EP Local H's Awesome Mix Tape #1:

(Local H's highest-charting modern rock single, 1996's "Bound For The Floor," peaked at #5. It's a 7.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the solo-electric "Joey" cover that the great indie lifer Ted Leo released in 2010:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Norah Jones playing a solo "Joey" cover at home during the early-lockdown days of March 2020: