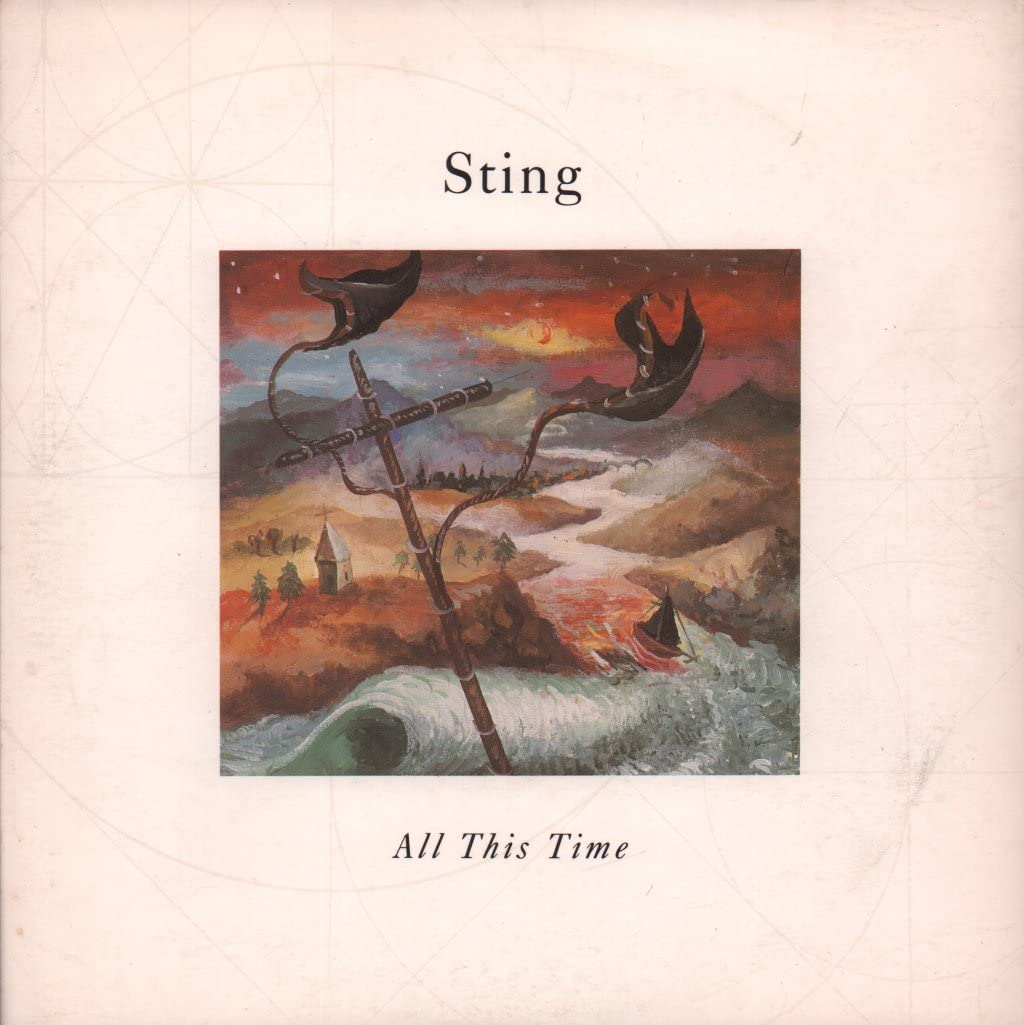

January 26, 1991

- STAYED AT #1:2 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

Here's what I don't get: How in the fuck was Sting ever considered alternative rock? Or even "modern rock," the radio format that existed before the term "alternative" entered widespread use? In past columns, I've talked about how maddeningly vague both terms are, but even without a fixed definition, I cannot reconstruct the line of thinking that allowed Sting to qualify. Sting is English and self-serious, and in the early days of alt-rock radio, that might've been enough to put him into contention. He had at least some vestigial connection to punk rock, and that probably helped, too. Even with all that in mind, though, I just don't see the connection. On modern rock radio, Sting must've always come off as the fusty adult in the room.

I'm not talking about the Police, mind you. With the Police, I get it. Those guys were always fake punks -- prog and jazz-fusion muso types who spiked their early sound up so that they could join the new wave hype-cycle. But it worked. The Police became probably the biggest stars of the Second British Invasion. Before "Every Breath You Take" became the biggest mainstream hit of 1983, the Police were a constant presence on college radio. In the '90s, I heard them all the time on my local alt-rock station's flashback-brunch show. I was never happy to hear them, but they were always there.

Solo Sting was different. The Police broke up soon after "Every Breath You Take" took over the world, and Sting took the first opportunity to leap headlong into the middlebrow rock aristocracy. You could see it coming a mile away. The Police had barely blown up when Sting started living the cliché rock-star tax-exile life. When his new wave peers were still trying to figure out how to move on with their lives, Sting was kicking it with Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler. He made music for people who owned CD players when only rich people owned CD players. He was a definitional '80s yuppie back in the days when most of the acts on modern rock radio were at least theoretically anti-yuppie. He didn't belong.

I can remember hearing Sting on alt-rock radio way back when I was first discovering my local station. I tuned in because I wanted to hear Nirvana and Pearl Jam and Faith No More, three bands that'll eventually appear in this column. Whenever Sting came on, I lunged for my little clock radio and switched over to the hair metal station, which was also playing all three of those bands. Back when my notions of cool were still mushy and unformed, I still didn't think Sting was cool. Really, I never have. Sting can be cool in movies. He's cool in Quadrophenia and Lock, Stock And Two Smoking Barrels and maybe Dune. Real life is a different story.

I've talked in past columns about how modern rock radio was a for-life thing. If you'd ever been considered alternative, you would always be considered alternative. That's how U2 appeared in this column even after they became a stadium-conquering phenomenon. It's how your Red Hot Chili Peppers and your Foo Fighters kept scoring massive alternative hits long after there stopped being anything remotely rebellious or exploratory about their music. Sting is actually the rare case where someone did get kicked out of the club.

When Billboard first started monitoring modern rock stations, Sting apparently qualified. By the time he was singing the Three Musketeers song with Bryan Adams and Rod Stewart, he was gone. Sting did something very difficult: He convinced alt-rock radio programmers to stop fucking with him. Before he pulled that feat off, though, Sting managed to go all the way to #1 on the modern rock chart exactly once.

The Police weren't technically broken up yet when Sting released his first solo album. In 1985, Sting rounded up a bunch of big-deal session musicians and jazz players, including Branford Marsalis, to record The Dream Of The Blue Turtles. (Funny title.) Sting was clearly already trying to push beyond new wave and, more generally, rock itself. Instead, he went for the kind of corporate-party slickster pop that was all over the charts right after the British haircut bands fell off.

Phil Collins played on some Blue Turtles demos, and I have to imagine that Sting was trying to get what Collins already had. For the most part, Sting got it, even though Blue Turtles lost the Album Of The Year Grammy to No Jacket Required. (Sting sang backup on a couple of No Jacket Required tracks, so he had that going for him.) Blue Turtles got enough critical respect to land on the Village Voice Pazz & Jop poll, and it went triple platinum. The LP also spun off a bunch of hits. The biggest of them, the vaguely dancefloor-friendly "If You Love Somebody Set Them Free," made it to #3 on the Hot 100.

In 1987, Sting followed The Dream Of The Blue Turtles with the double album ...Nothing Like The Sun. (Ellipses his.) Sting recorded that one in Switzerland, going for an ultra-digital polyglot-pop type of sound. I listened to that album for the first time while writing this column, and I did not have a good time with it. Nevertheless, Sting had another success on his hands. ...Nothing Like The Sun went double platinum and scored another Album Of The Year nomination. (Sting lost that one, quite justifiably, to George Michael's Faith.) The record just barely made the Pazz & Jop list, and it had some hits. "Englishman In New York" is the best-known song from that album today. At the time, though, the biggest performer from ...Nothing Like The Sun was the godawful quasi-funk throwdown "We'll Be Together," which was literally written for a beer commercial and which made it to #7 on the Hot 100.

When Billboard started up the Modern Rock Songs chart in 1988, Sting's ...Nothing Like The Sun album cycle was technically still happening, so I suppose it's notable that none of its songs ever touched that chart. Maybe that stuff was too commercially craven to share airtime with Siouxsie & The Banshees, or maybe the hype around that album had just died down enough. In any case, Sting's third solo LP, 1991's The Soul Cages, was not a naked mainstream-radio play. Instead, it's a concept album about the death of Sting's father. The record still sounds bright and expensive and digital, but the sentiments are heavier and more grief-stricken. Maybe that's why modern rock radio welcomed Sting. Maybe the former King Of Pain made some sense next to the Cure.

Or maybe not. If The Soul Cages worked in conversation with any of the other stuff on modern rock radio in 1991, I can't hear it. It's a whole lot closer to the music that guys like Phil Collins and Bruce Hornsby, Sting's real peers, were making around the same time. Sting recorded The Soul Cages in France and Italy, and his producer was Hugh Padgham, one of the pioneers of Collins' trademark gated drum sound. Padgham worked with the Police and with Sting on ...Nothing Like The Sun, and he was the prime collaborator for Collins and Genesis during their remarkably lucrative '80s run. The Soul Cages sounds like a Hugh Padgham record.

Sting's backing band on The Soul Cages included Dominic Miller, a hotshot guitarist who'd been a touring member of World Party and who remains with Sting today. It's also got a bunch of the studio aces who played on past Sting records -- Bradford Marsalis, Kenny Kirkland, Manu Katché. If you're looking for any trace of jangle-pop or shoegaze or acid house on The Soul Cages, you might have to keep looking for a long time. If Sting was listening to any of that stuff, he kept its influence from leaking through. Instead, it's an album rich in drum echoes, pan flutes, and antiseptic guitar chimes. That sound has its partisans, but it's not for me.

You know who loves this stuff? Stereogum founder Scott Lapatine, my boss. Scott has identified "All This Time," the lead single from The Soul Cages, as one of his favorite songs of all time. Scott's got a Sting tattoo. Back when Stereogum had corporate parents, he once got Sting (and Shaggy) to play a promotional set in the office that we shared with Billboard and SPIN and some other publications. (I wasn't there.) Since I have no feel for this music and since Scott loves it so much, I asked if he wanted to write a guest-column this week. He couldn't -- too busy, he says -- but he did drop a few words about it into our Slack channel. I'm quoting it with his permission:

I acknowledge that this is very much my shit and you'll think it's Sharper Image Rock. Sting's first three solo albums utilized fussy, polished production in a way I find very engaging, especially when it comes to rock music played by incredible jazz musicians. (Hugh Padgham also produced my favorite Genesis album, the self-titled one.) There are like a dozen virtuosos playing on "All This Time." I love Dominic Miller's alternating muted/ringing guitar lines, love hearing Kenny Kirkland and David Sancious on the same track, love the sound of a mandolin always. It's a jubilant-sounding song, but was inspired by Sting's father's death. The first few verses describe a funeral, then it zooms out after the key change to present a sort of black comedy about the folly of cultural institutions. It was also part of an affecting concept album set against the Newcastle shipyards of Sting's youth, which eventually became a musical I didn't like because I don't like musicals. Over the years Sting wrote a lot of ambitious pop music that slyly interpolated Bach, Prokofiev, Eisler, etc. He did that here and it's like, an easter egg for annoying people (me)? And he sings about shire horses and garrison towns and makes it not sound labored and sometimes I need a dictionary? I understand why people think this is all pretentious, but I admire the intricacies of Sting’s songwriting. His work got less serious after The Soul Cages, and I liked it less and less. “All This Time” was the first solo song of Sting’s I became cognizant of, but I’m surprised it was an Alternative #1! I discovered it on VH-1.

Sting was already a grown-up when the Police started, and he was just shy of his 40th birthday when he released The Soul Cages. He wrote "All This Time" while staying in Marcel Proust's old room in Normandy, and he took the melody from a Bach cello suite -- two facts that, combined, are so pretentious that they almost just caused my laptop to burst into flames. To his credit, Sting acknowledged his own pretension when he talked about the song. When he wrote it, he was thinking about his father, his father's burial, and the town where he grew up, and all those things kind of blurred together in his lyrics.

Here's how Sting once described his father's passing: "We'd had a difficult relationship, and his death hit me harder than I'd imagined possible. I felt emotionally and creatively paralyzed, isolated, and unable to mourn. I just felt numb and empty, as if the joy had been leached out of my life." I can actually relate to all of that. Every word. I lost my dad a couple of years ago, and it was a bad time. My father, like Sting's, was a devout Catholic. On "All This Time," Sting sits through his father's Last Rites, and the religious talk flows right past him. He imagines burying his dad at sea instead. That's pretty much how I felt when I sat through my dad's funeral. The priest was an old family friend, but I didn't recognize my father in a single word that guy said. At least for me, none of the ritual around my father's death had any meaning at all. So it goes.

Sting grew up in Wallsend, a shipping town near Hadrian's Wall. His "All Time Time" lyrics are full of images of that town -- seagulls, fog, sad shire horses, sodium lights. While Sting half-listens to priests saying the things that priests say, he thinks about the river that flows through town -- how it's been flowing since long before Sting and his father were there, how it'll keep flowing long after. The beliefs of the humans in this town are temporary, but the river is eternal. Back when Wallsend was a Roman outpost, the people living there had their own beliefs, and the river outlived all of them: "They lived and they died/ They prayed to their gods, but the stone gods did not make a sound/ And their empire crumbles till all that was left were the stones the workmen found."

Hey, that's heavy shit! If "All This Time" was a very different song -- one that sounded nothing like solo Sting -- then I might really get something out of it. Unfortunately, it's not a different song. It's this song. I just can't handle this stuff. It's not that I hate "All This Time" and songs like it. It's that this music slides right past me. It gives me nothing. It's a faint ear-tickle, and then it's gone. The writing might be rich, and the production might be layered, but I'll never remember anything about it. It won't even leave a ghost of an impression on me. I couldn't hum this motherfucker with a gun to my head.

There's stuff on "All This Time" that I could theoretically get into. There's a slight Irish-folk thing going on in the arrangement, at least early in the track -- some mandolin, some pipes. There's a guitar that jangles without ever going full R.E.M., so perhaps I was lying when I said that there's no jangle-pop on The Soul Cages. There's an organ that's clearly shooting for soulfulness, and then there's a moment where it gets a little more urgent and the drums get faster. But it still sounds cluttered and off-puttingly clean at the same time. I bet baby boomers used to test hi-fi systems with songs like this. To me, it's just gruel.

You guys into Sting's singing voice? Somebody must be into it. I don't get it. Even when the guy sings about bottomless personal pain, he sounds vaguely pinched and smug. For a guy who loves tantric sex so much, Sting just never sounds relaxed. He's got a bleat that reminds me of the most self-regarding parents at my school when I was a kid. Maybe this isn't Sting's fault. Maybe I'm bringing personal shit to this review. Maybe I have some deep-seated association with the lady who had the first car phone I'd ever seen and who smacked me in the side of the head when I pressed the hang-up button. I just can't get into this shit. Sorry.

The "All This Time" video seems like it should be fun. It's got Sting cavorting with French maids on a boat, and it's supposed to evoke a classic scene from the Marx Brothers movie A Night At The Opera. One of the French maids is Sting's partner Trudie Styler. (They already had a couple of kids by this point. They got married in 1992, and the Police reunited to play the wedding.) The other is real-deal Hollywood babe Melanie Griffith. She and Sting starred in the movie Stormy Monday together in 1988. Never saw that one. The video's director is Alex Proyas. Later on, he made The Crow and Dark City, two movies that I really like, and also some pictures that I don't like that much. So here we've got Melanie Griffith in an Alex Proyas music video that's based on a Marx Brothers film, and it's boring? How does that happen? I blame Sting.

"All This Time" was a big hit. It went to #1 on the mainstream rock chart, #9 adult contemporary, #5 on the Hot 100. Sting's follow-up single "The Soul Cages" was a total flop in a mainstream sense, but it still made it to #9 on the Modern Rock chart. (It's a 4.) The Soul Cages went platinum, but it didn't sell as well as Sting's previous two albums. It was Sting's first solo LP that didn't get an Album Of The Year Grammy nomination or make it onto the Pazz & Jop poll. You could argue that the other Sting had a better 1991, since he spent the year feuding with Ric Flair, the Steiner Brothers, and Paul E. Dangerously's Dangerous Alliance.

Sting came back with the hugely successful 1993 LP Ten Summoner's Tales, which went triple platinum and snagged Sting's final Album Of The Year nomination. (He lost that one to the Bodyguard soundtrack.) At that point, alternative radio still claimed Sting, even with grunge in ascendance. Lead single "If I Ever Lose My Faith In You" peaked at #4 on the Modern Rock chart, and I definitely remember hearing that one on the radio. (It's a 5.)

"Fields Of Gold," the second Ten Summoner's Tales single, was the last Sting song to make it onto the Modern Rock chart; it peaked at #12. "Shape Of My Heart," from the same album, didn't land on the Modern Rock chart, but it did serve as the basis of the late emo rapper Juice WRLD's 2018 breakout hit "Lucid Dreams," so that's something. (Juice WRLD's only Alternative Airplay hit, the posthumous 2020 Marshmello collab "Come & Go," peaked at #7. It's a 6.) By the time 1993 was over, Sting was remaking the Police's "Demolition Man" for the Stallone movie of the same name, so maybe that's why modern rock programmers started ignoring him. I hope that's not the reason, though. That movie fucking rules.

The real reason is probably "All For Love," the Bryan Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting song that topped the Hot 100 in January 1994. When that song is out in the world, you can't really sell those guys to America's alt-rocker kids -- not with Smashing Pumpkins and Alice In Chains running around. Sting has remained hugely successful in the years since then, even if he hasn't made a lot of chart hits. He gets all that Puff Daddy money, and he can still play himself on Only Murders In The Building or whatever. On 9/11, he taped a live album called All This Time for a bunch of fan club members at his Tuscan villa. That must've been a weird vibe. Sting seems to be doing great these days. Shout out to him. I'm glad we don't have to pretend that he's an alternative rocker anymore.

GRADE: 5/10

BONUS BEATS: In 1995, Sting released a CD-Rom called All This Time. This video is a chilling, nostalgia-annihilating reminder of the kind of shit that we used to have to deal with:

THE NUMBER TWOS: Chris Isaak's soft-focus, vaseline-smeared hornball hymn "Wicked Game" peaked at #2 behind "All This Time." Nobody loves no one, but I love this song. It's a 10.