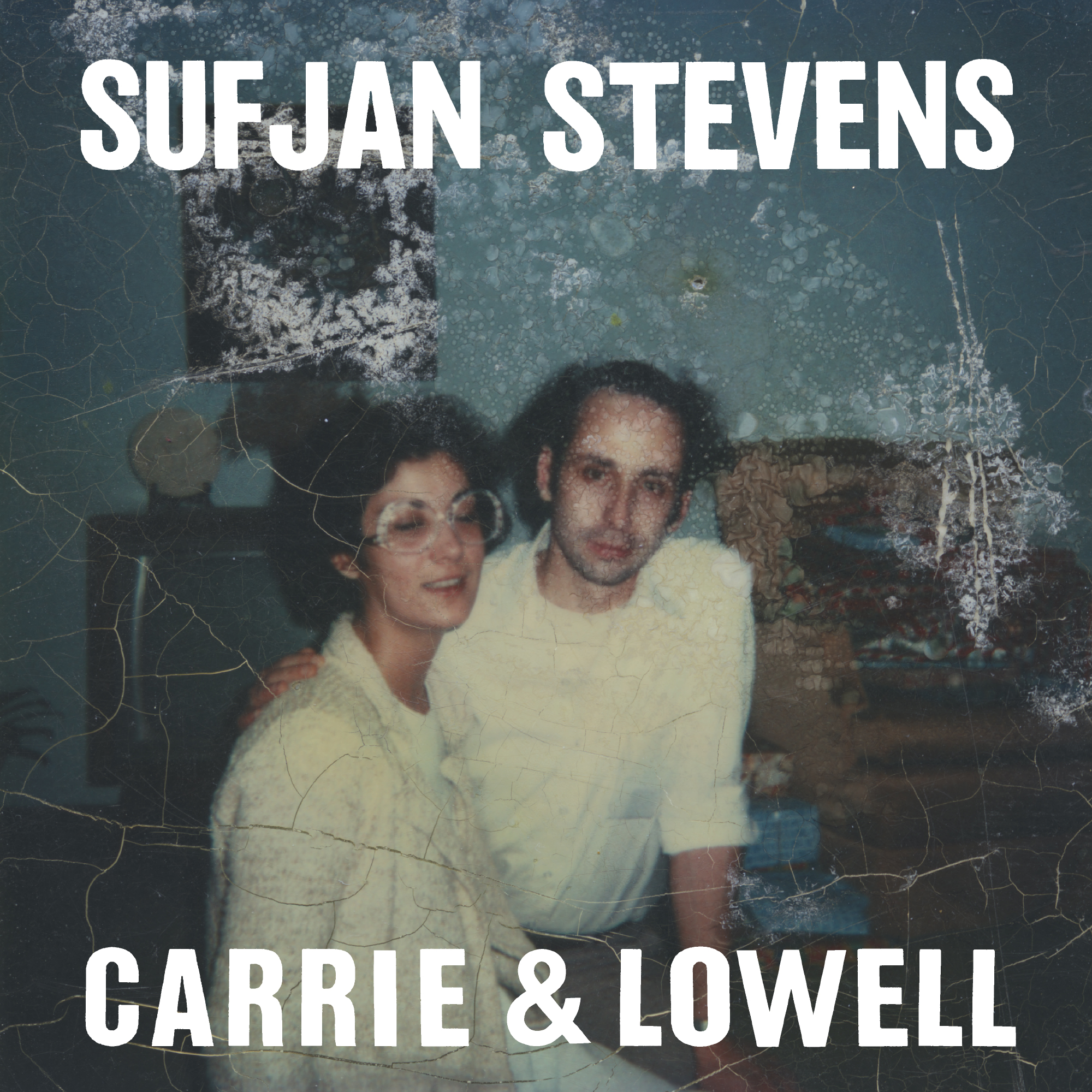

- Asthmatic Kitty

- 2015

I hope you can't relate to Carrie & Lowell. I hope, like me, you have no idea what it feels like to be abandoned by your mother, to spend decades estranged from her, to have your grief about her death tainted by your shame about her life. Lord willing, when you listen to the album Sufjan Stevens released 10 years ago today, you do not hear your own story reflected back in it. The overwhelming despair and confusion captured here are feelings that should not be thrust upon you by someone else's choices, least of all someone who is supposed to nurture and protect you. And yet, in this broken world, the trials chronicled by Stevens here resonate with far too many.

People would have gravitated to Carrie & Lowell even if Stevens' experiences were entirely unique. The music is simply too beautiful to be ignored, even if — with their hushed vocals and arrangements so sparse they seem more spiritual than physical — the songs are not exactly screaming for your attention. Stevens was probably joking when he called the album "easy listening," but it really did go down smoothly. It was all so gorgeous, in such an accessible way, that Carrie & Lowell inevitably became a soundtrack for the network-primetime version of family drama, with prestige-Hallmark series This Is Us using opener "Death With Dignity" in its pilot and plenty of other shows synching songs from the tracklist. The sad and ghostly aesthetic also wielded a powerful influence on the generation of indie singer-songwriters that proliferated over the past decade, most notably echoing throughout Phoebe Bridgers' Punisher, an album that basically became a genre unto itself.

Carrie & Lowell was a monumental release even before it rippled out into the mass consciousness and imprinted itself on the zeitgeist. Upon release, it was widely received as a masterpiece — the best work of Stevens' career, per Brandon Stosuy, whose Best New Music-bedazzled Michigan review had launched Stevens to indie stardom 12 years prior. The lyrics were achingly raw yet sculpted with a careful hand, performed with trembling gentleness and dead-eyed resignation, backed by strumming and plucking that seemed to spill from a mirage thanks to the ambient glow that became the backdrop for most tracks. In one sense it was as meticulously produced as any of Stevens' albums, but it was also pure, uncut Sufjan: the album his fans had been craving for years, a Bandcamp-era update on the style that made him the preeminent balladeer of Myspace-era indie.

The biography behind Carrie & Lowell has become the stuff of myth. Sufjan, the youngest of six siblings, was just one year old in 1976 when his mother, Carrie, left the family. The Stevens kids were raised in Michigan by their father, Rasjid, and Sufjan's stepmom, Pat, and only maintained fleeting contact with Carrie. But when she married her high-school sweetheart Lowell Brams four years later, Lowell made it a point to reconnect with her kids, and the children spent three summers with Carrie and Lowell in Eugene, OR during what were supposedly the most stable years of Carrie's life.

"She was a good mother when she had her facilities together," Stevens told Laura Snapes in a 2015 Uncut feature. "And she had nothing but love for us and the best intentions. But she was really sick. She was very dysfunctional and she had substance-abuse problems – she was an alcoholic and a drug addict – and schizophrenic, bipolar, really depressed. We were aware of that, even as children. So we were very grateful for the limited time that we had with her, and we knew that it was finite. We had no delusions or expectations."

After Carrie and Lowell divorced in 1984, she disappeared from her children's life again, but Lowell, who'd fed young Sufjan's hunger for music with a steady supply of cool records and creative outlets, remained in touch. (He co-founded the record label Asthmatic Kitty with Stevens in 1999 and continues to run it from Wyoming.) As an adult, Stevens only saw his mom occasionally, and neither party made much effort to be close. In 2012, he learned from an aunt that Carrie was in the ICU without much time left. He spent a few days with her in the hospital before she passed, then distracted himself from his mourning with a flurry of creative projects, from hip-hop to ballet. Eventually, he began confronting his gnarled tangle of feelings in song, but even then, he wasn't sure if they were any good until he brought the material to Thomas Bartlett, aka Doveman, whose own brother had recently died from cancer.

"Thomas took all these sketches and made sense of it all," Stevens told The Guardian. "He called me out on my bullshit. He said: ‘These are your songs. This is your record.' He was ruthless." Spurred to action, Stevens traveled the country working on the album, fitting in recording sessions in locales like Portland (with his old friend and peer Laura Viers) and Wisconsin (at Justin Vernon's April Base Studio) between biking and camping trips across wide-open states out west. "I was just travelling a lot and working with other people because it was convenient and I wanted to engage socially lest I lose myself in isolation," he told Uncut. "A lot of those people and their participation, it really fed me, fueled me, encouraged me."

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

At the time, Stevens' most recent proper album was 2010's The Age Of Adz, a maximalist electronic freakout with an elaborate space-age-community-theater stage show to match. He'd since busied himself with extracurricular projects esoteric and outre, leaving fans to wonder if the Sufjan they first fell in love with was gone for good. In that context, Carrie & Lowell felt like a huge deal — all the more so because of how small it seemed, paring back all those sonic and conceptual layers, leaving its wounded auteur in darkness under a faint spotlight. "For so long I had used my work as an emotional crutch," Stevens told Uncut. "And this was the first time in my life where I couldn't sustain myself through my art. I couldn't solve anything through my music any more. Maybe I had been manipulating my work over all these years – using it as a defense mechanism or a distraction. But I couldn't do that any more, for some reason."

The album was billed as a return to the acoustic folk sound associated with Stevens' mid-aughts breakthrough, specifically the barebones intimacy of 2004's Seven Swans, but that comparison wasn't quite right. These songs were similarly up-close-and-personal, arguably even more so given the personal mess Stevens was airing out. But he was a different person now: older, wiser, the brightness in his eyes dimmed by the years. Gone was the twee precociousness that seasoned Stevens' early work. The production was different, too. The dry and direct Seven Swans sounds like a demos collection compared to Carrie & Lowell’s swaddled-in-celestial-light vibes. In interviews, Stevens talked about feeling haunted, even possessed by his mother's spirit — "Your apparition passes through me!" he sings on "Death With Dignity" — and these songs sound way more like spectral visitations than open mic night.

"There's only a shadow of me/ In a manner of speaking, I'm dead," Stevens declares amidst the percussive pulse of "John My Beloved," encapsulating the Carrie & Lowell aesthetic in one quick burst of poetic language. Stripping away the ambitious concepts and the ostentatious arrangements, our narrator had constructed impossibly lovely prisms through which to peer in at his painfully human struggles. "Fuck me, I'm falling apart," he harmonizes on "No Shade In The Shadow Of The Cross," lamenting the absence of divine consolation. "You checked your texts while I masturbated," he casually intones on "All Of Me Wants All Of You," crossing new boundaries of personal disclosure. "I just wanted to be near you," he sings, with a boyish daintiness, flashing back to those Oregon summers on "Eugune." Those snapshots of childhood make it all the more heartbreaking when, on the solemn piano ballad “Blue Bucket Of Gold,” Stevens pleads with his dead mother, “Raise your right hand/ Tell me you want me in your life.”

The lyrics were startling in their simplicity, their directness, their lack of obfuscation. The music was similarly striking, blessed by a less-is-more approach that elevated the songs without getting in the way of Stevens' attempts to lay it all bare. He'd sung to God many times before, but never had his songs felt more like desperate prayers. Even more crushing than his questions for the Lord are the ones issued to Carrie: "Did you know me at all?" and "Can we be friends?" and, oh wow, "Why don't you love me?" One of those queries doubles as a thesis statement for the project: "How do I live with your ghost?" When the closing track crosses over into its celestial coda, it's still not clear whether he'll ever find the answer.

Life has not gotten easier for Sufjan Stevens. His father died in 2020, inspiring another grief-stricken creative outpouring in the form of the 49-track instrumental album Convocations. After decades spent dodging questions about his love life, upon the release of 2023's Javelin, he dedicated the album to "the light of my life, my beloved partner and best friend Evans Richardson, who passed away in April." At the time, Stevens was hospitalized with Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune condition that left him hoping he'd learn to walk again within a year. All throughout, he has continued to release powerful, affecting music — projects that have been received as gifts by listeners who've caught glimpses of their own fragility in the songs, whether or not they directly mirror our own experience.

None of them, though, has resonated quite like this vulnerable dispatch from the brink of desolation. Unguarded in its ugliness yet breathtaking in its beauty, Carrie & Lowell continues to quietly reverberate a decade later. I don't know if it's the best Sufjan Stevens album, but in ceasing to hide behind pageantry and allegory, it's the one that most pristinely and succinctly captures the agony of life on Earth. Regretfully, it rings true.