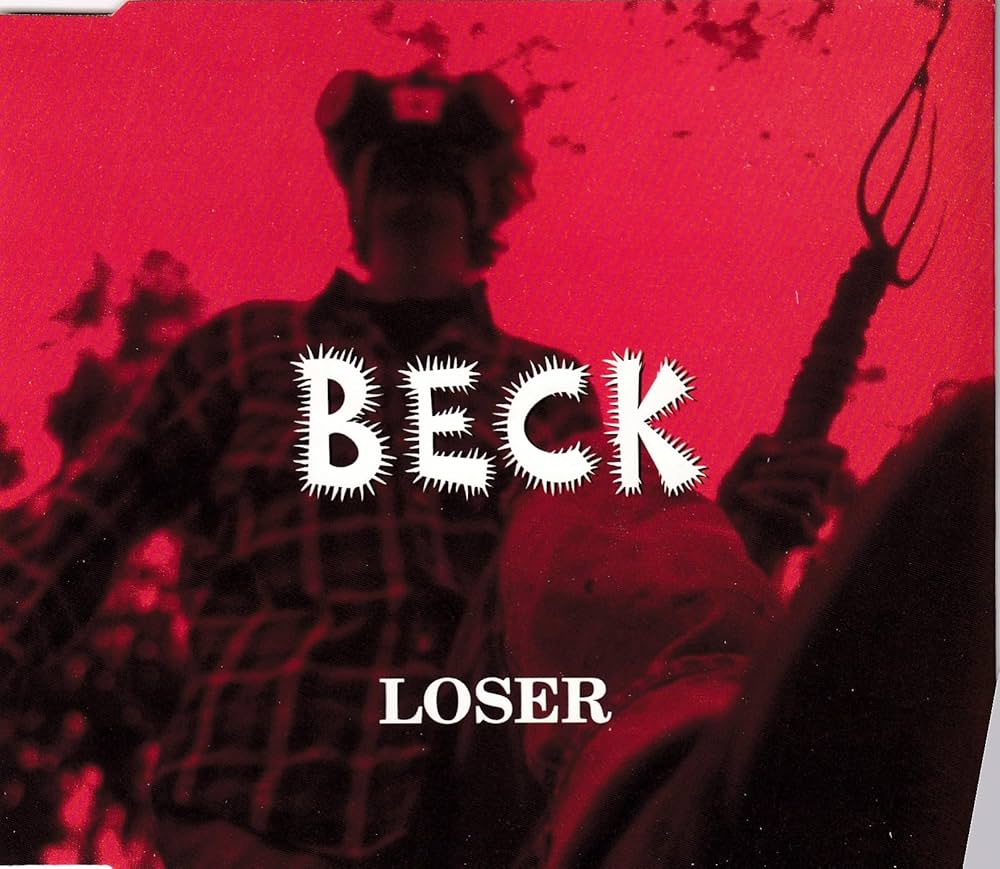

February 5, 1994

- STAYED AT #1:5 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

In the time of chimpanzees, he was a monkey. Or maybe we were the monkeys. Maybe the divisions between chimpanzee and monkey are made-up and meaningless, like the mega-publicized generation gaps in which entire swaths of the American population are depicted as apathetic schlubs who spend all day sitting around, watching '70s sitcom reruns with Cheeto dust all over their fingers. Maybe the phrase "in the time of chimpanzees, I was a monkey" is crucial for understanding the popular culture of the 1990s, or maybe decades are just an arbitrary way of measuring time telling us nothing of value. Maybe time is a piece of wax falling on a termite, and it's choking on a splinter. There are so many possibilities to consider. If you think about Beck's "Loser" too hard, you might break your brain.

The magic of Beck's "Loser" is that Beck never thought about "Loser" too hard. In many ways, "Loser" is the most influential song that's appeared in this column since "Smells Like Teen Spirit." In many ways, it's the antithesis of that song, even though Beck and Kurt Cobain had the same haircut. Today, "Loser" might as well be "Smells Like Teen Spirit," since both songs are so overplayed and historically significant that I'll never be able to properly enjoy either of them again, even though I loved them both when they popped up in radio rotation during my middle-school years. Cobain never had any inkling that "Teen Spirit" would be as huge as it was, but he was still trying to write a successful rock 'n' roll song. Beck was just fucking around in somebody's kitchen, and the success of "Loser" surprised him more than anyone.

The just-fucking-around aspect is key to the appeal of "Loser." As soon as his career started, Beck started facing the same generational-spokesman speculation that drove Kurt Cobain so crazy. With Beck, there was an extra layer of dissonance, since "Loser" became known as a song for so-called slackers, as if the principal from Back To The Future was handing out sobriquets. Beck bristled against that and claimed that he'd never been a slacker in his life. Instead, the indelible "Loser" hook was just Beck's self-deprecating joke about his own inability to rap like Chuck D from Public Enemy. But authorial intent is a red herring. It doesn't matter what Beck meant. It matters that he made a fun, catchy song that allowed vast numbers of kids to sing, proudly and happily, about being losers. Accidentally, Beck made the kind of generational anthem that nobody could've made intentionally.

"Loser" is one of those great old-school pop-success stories. Like "96 Tears," it's a lo-fi, home-recorded lark that caught on gradually and unexpectedly, spreading from one radio station to the next, scratching some invisible public itch. Unlike ? And The Mysterians, Beck gradually evolved into a music-business fixture with a wall full of gold records and a mantle full of Grammys. The surprise success of "Loser" means I finally get to write one of these columns about someone who wasn't tortured by success or addiction or the music business as a whole. Beck looked at pop stardom as a fun, weird adventure, not as an existential soul-weight. He told us that he was a loser, and then he won.

When Beck first became an alternative rock poster boy, he insisted that he didn't have anything to do with alternative rock. As early as 1988, Nirvana's old label Sub Pop was selling T-shirts that said "LOSER," and those things were underground-omnipresent for years. The idea of the LOSER shirt, much like Richard Linklater using Slacker as the title of his first film, was to own the label that people would've inevitably given you anyway. But that wasn't Beck's style. In the first of many SPIN cover stories on Beck, writer Mike Rubin captures the young star at work in the Los Angeles venue that his mother co-owned, playing one of the first sloppy-ass shows with his newly assembled band. That night, Beck asked the crowd a couple of rhetorical questions: "What’s with these ‘LOSER’ T-shirts? Don’t you people have any self-respect?"

Though he didn't exactly make the early-'90s radio version of alternative rock, Beck was almost literally born into the underground. Beck's maternal grandfather Al Hansen was part of the '60s conceptual art movement Fluxus, which was apparently a big deal even though I have mostly encountered the word "Fluxus" in magazine articles about Beck. For a little while in the '80s, Al Hansen also managed LA punk band the Controllers. Beck's father David Campbell was an LA studio musician in the '70s, playing on Marvin Gaye and Bill Withers records and doing arrangements for Carole King. Campbell composed the scores for '80s movies like All The Right Moves and Night Of The Comet, and he's still working as a Hollywood orchestrator today. Beck's mother Bibbe Hansen was a Factory regular who acted in a few Andy Warhol films. When Beck was a kid in the late '70s and early '80s, Bibbe would let LA punks like Darby Crash sleep on the couch in the family's apartment.

Beck's family has lots of fancy art-world pedigree, but he didn't grow up rich. Instead, he spent his childhood in relative squalor with his mother in East Los Angeles, sometimes shuttling off to spend time in Kansas with his Presbyterian-minister grandfather -- not Al Hansen, the other one. Beck's mother was apparently fine with him dropping out of school after eighth grade, which is absolutely something I would've done if the option was available to me. As a kid, Beck found a Mississippi John Hurt record at a friend's house, and he fell in love. He found an acoustic guitar and tried to make his own folk-blues music. Sometimes, he'd go out and busk in a neighborhood park. Later on, he told SPIN, "There would be these Salvadorian guys playing soccer and this little white boy playing Leadbelly songs. Nobody would listen. It was really pathetic."

Beck started making tapes at home. After discovering noise-rock bands like Sonic Youth and Pussy Galore, he'd mess around with tape speeds, making his voice more abrasive and unnatural. On the internet, you can find tape-rips of the stuff that Beck made as a teenager, though it's not really a worthwhile exercise for anything other than historical purposes. In 1989, the 19-year-old Beck followed a girlfriend to New York. The couple didn't stay together for long, but Beck bummed around the Lower East Side for a couple of years. He latched onto the city's anti-folk scene, a punk-inspired DIY art-folk universe built around the singer-songwriter Lach. He didn't find fame there, but the freeform nature of that scene made an impression on him.

In 1991, Beck returned to Los Angeles and drifted from one odd job to the next. He worked the counter at a video store. He painted signs. He handed out hot dogs at kids' birthday parties. All the while, he kept working on music, playing on any stage that would have him. Beck loved rap, hearing it as an extension of the Delta blues that influenced him so deeply. History proved him right on that. Scarface, a past collaborator of "Loser" co-producer Karl Stephenson, makes a lot more sense if you hear him as part of the same lineage as Robert Johnson. Sometimes, Beck would try to capture disinterested audiences by pulling people up to beatbox while he rapped half-assedly in between acoustic folk songs. Sometimes, he'd just go up there and make terrible noise. When Beck got a job blowing leaves, he'd bring his leafblower up onstage and use it as an instrument.

Eventually, producers Tom Rothrock and Rob Schnapf caught a Beck set at the DIY venue Jabberjaw, and they were into it. Those guys ran Bong Load Records, an LA indie that put out records by bands like Wool and Fu Manchu. Later on, Rothrock and Schnapf co-produced the last three Elliott Smith albums, and Rothrock recorded the SpongeBob Squarepants song "Goofy Goober Rock." I don't know what to do with this information, so I am simply presenting it to you. Do with it what you will. The Bong Load guys knew that Beck loved rap, so they put him in touch with their acquaintance Karl Stephenson.

Karl Stephenson -- sometimes listed as "Carl" -- is a DC native who ended up in Houston as a 19-year-old in the mid-'80s. Somehow, Stephenson linked up with Rap-A-Lot Records, the legendary Houston label, and started working with the Geto Boys, arguably the most important Southern rap group in history. When Stephenson entered their orbit, they were still known as the Ghetto Boys, and Scarface and Willie D weren't even in the group yet. Stephenson produced most of the Ghetto Boys' 1988 debut Making Trouble, and he kept making music with them for a couple of years, but he got sick of working for Rap-A-Lot and moved to LA in 1992. That's when the Bong Load guys brought Beck to his house. When he met Beck, Stephenson was making beats for Paula Abdul's cartoon collaborator MC Skat Kat. This seems like a joke. It is not. (Later on, Stephenson led the LA band Forest For The Trees, whose only Modern Rock hit, 1997's "Dream," peaked at #18.)

The fateful "Loser" recording session went something like this: Beck went over to Stephenson's house one day in 1992, and he played some of his songs for Stephenson. Then, he messed around with a little slide-guitar riff. Stephenson recorded that riff and turned it into a loop. Then Stephenson set that riff to a breakbeat. He used the shuffle-sliding intro drums from bluesman Johnny Jenkins' 1970 cover of "I Walk On Gilded Splinters," a song that Dr. John wrote and recorded a couple of years earlier. That Jenkins record is fire, and its breakbeat had already appeared on tracks like Chubb Rock's "Bump The Floor," PM Dawn's "Comatose," and the Geto Boys' "Gangster Of Love," which is not one of the Geto Boys tracks that Stephenson produced. When Stephenson had the beat together, Beck attempted to rap.

Beck wanted to sound like Chuck D. That's what he told SPIN, anyway. Maybe he was joking. It's often hard to tell if he's joking. But that shit is funny, whether or not it was supposed to be. If Beck said he was trying to rap like Q-Tip, I'd be like, "Well, no, but OK." Chuck D is a different thing. Like Chuck D, Beck has a deep voice, but that's the absolute end of the similarities. Chuck is booming, authoritative, commanding. Beck is none of those things. He raps in a sideways drawl, as if he's smirking a wisecrack that you don't get. I can stretch to say that there might be a little bit of self-conscious racial anxiety in his delivery. Every once in a while, Beck will say something that an actual rapper might say, just as an aside -- "yo, cut it" -- and that'll always come off awkward. Mostly, though, Beck just sounds like he's having his own deeply idiosyncratic form of fun.

I haven't mentioned the lyrics yet, mostly because I don't know how to discuss the lyrics. It's been 31 years, and what can I possibly say? Beck's words are dizzy, surreal, free-associative. They don't necessarily mean anything, but the wording is vivid and satisfying anyway. It does something to my brain. "Forces of evil in a bozo nightmare." "The rerun shows and the cocaine nosejob." "Baby's in Reno with the vitamin D." "Don't believe everything that you breathe, you'll get a parking violation and a maggot on your sleeve." Does any of that mean anything? Probably not, right? But those lines have all been buzzing in my head like static since I first heard them, half a lifetime ago.

Legend has it that Beck listened to those verses of poetic gibberish and decided that he sounded like ass. When he sang that chorus -- "Soy un perdidor/ I'm a loser, baby, so why don't you kill me?" -- he was just making fun of his own rapping, not trying to make some generational statement. He has told that story again and again, and it hasn't really changed. Here's how he put it in that first SPIN story: "When they played it back, I was like, 'I’m the worst rapper!' So when I did the chorus, I was just putting myself down." Even if that chorus is just offhand self-mockery, it sticks. He sings it with a sense of loopy silliness, and that loopy silliness was just the ticket at the peak grunge era. "Loser" seemed to traffic in the same over-it irony that B-list grunge band like Mudhoney might employ, but Beck's version was a whole lot catchier and friendlier. Beck could sing about being a loser without the slightest hint of self-hatred. In 1994, that felt oddly revolutionary.

"Loser" is a strange little bolt of inspiration, a thing that couldn't be repeated. It's funky blues and deadpan joke-rap and experimental noise-rock all at once, and that combination somehow registered as alternative rock, and then as straight-up pop music. Nobody could plan that. Officially, Beck and Karl Stephenson are the writers of "Loser," and those two guys and Tom Rothrock are the producers, though I don't know what Rothrock did. Beck and Stephenson finished the track up in a few hours, and then they had to be done because they were recording in Stephenson's kitchen and his wife wanted to cook dinner.

Beck didn't know what he had with "Loser." Nobody knew. The song had to reveal itself over time. Beck finished recording that song, and he went right back to his underground-eccentric life and forgot all about it. In 1993, Beck put out Golden Feelings, a full-length tape that's now considered his debut album even though it barely ever existed. He dropped a folky novelty single called "MTV Makes Me Want To Smoke Crack," which I heard on the radio a few times after "Loser" blew up. Eventually, the Bong Load guys convinced a skeptical Beck that they should release "Loser" as a 12" single, and they pressed up 500 copies in 1993.

A couple of college radio stations in LA started playing the "Loser" single, and then the alt-rock giant KROQ picked the song up and put it into heavy rotation. (In the SPIN cover story that I keep referencing, Beck plays "Loser" live and introduces it as "KROQ Set My Dick On Fire.") Up and down the West Coast, other commercial alt-rock stations started playing the song. Later on, Beck told Mike Rubin, "These really heavy-duty commercial stations [started] playing it. They didn’t even have copies. They were making cassette copies off of someone who had a copy of the vinyl... They were playing it on the radio and I heard it, and they said ‘This is the slacker anthem,’ and immediately it just clicked and I thought, 'Oh shit, that sucks.'"

I must've first heard "Loser" during that time. The DJs on WHFS, my own local alt-rock station, were talking about this crazy, funny new song. One of them seemed really weirded out that the guy who made the song simply called himself Beck. He said something like, "That's like calling yourself 'Stones'" -- as if Jeff Beck owned all rights to his last name. They didn't say "slacker," but I must've thought it anyway. It was impossible to not draw that connection. The word was floating around in the zeitgeist, and this guy rapping sloppily and declaring his loserdom fit right into a brand-new cultural archetype. Beck never sounded like he was trying to make slacker music, but that would be impossible anyway. If you were trying to make slacker music, then you were failing, because slackers don't try.

Also, slackers are not real. People can be lazy bums if they want, but it's not a lifestyle or a subculture. It's just a thing that people sometimes do. Beck heartily objected to the label whenever anyone used it. Here's what he had to say about it in SPIN: "You’d have to be a total idiot to say, 'I’m the slacker generation guy. This is my generation, we’re gonna fuckin’ -- we’re not gonna fuckin' show up.’ I’d be laughed out of the room in an instant... I’ve always tried to get money to eat and pay my rent and shit, and it’s always been real hard for me. I’ve never had the money or time to slack."

Whatever Beck's intentions, the "slacker" tag definitely helped his noise-rap novelty song spread across the world, first as a cult hit and then as an actual hit. Beck and indie-film director Steve Hanft spent $300 making a "Loser" video, but it wasn't finished for a long time because it took way more money than that to develop the 16mm film. Hanft's voice is on the song, too. He's the person says, "I'm a driver, I'm a winner." It's dialog sampled from his 1991 indie film Kill The Moonlight, which shares its title with the best Spoon album. I always figured that voice was George Bush, but no, it was Steve Hanft.

The "Loser" video is a near-perfect combination of form and content. Much like the song itself, it seems to be nothing but a loose, sloppy barrage of surreal imagery. The Grim Reaper peeks in through somebody's car windshield. Two astronauts sit on the back of a pickup truck. A coffin magically propels itself through the parking lot of a check-cashing place. An adorable little girl plays drums. Beck stares, happily slackjawed, into the middle distance. When MTV got ahold of the "Loser" video, the network went crazy with the Cheez Whiz. I didn't even have cable when "Loser" was out, and every frame of that video is deeply embedded in my brain.

Naturally, major labels went nuts for Beck. He was an unsigned kid with a viral hit, back when that was still a relatively rare pre-internet phenomenon. Beck wanted to stay on Bong Load, but Bong Load couldn't keep up with the demand for physical copies of "Loser." A major-label bidding war broke out, and Beck got to talking with Geffen, the same label that signed Nirvana and so many of that moment's other alt-rock acts. Geffen offered Beck a whole lot of artistic freedom, but he was still ambivalent about the deal. In a 2011 Pitchfork interview, Beck told my friend Ryan Dombal, "I didn't want to be on a major label. I wanted all the attention and the noise to go away because I wanted to be something a little bit more substantial... I just ignored it for six months and thought it would go away. I told all the labels no, or had stopped returning their calls." But the people at Geffen came from the '80s indies, and they seemed to get where Beck was coming from. He signed.

In January 1994, Geffen put up the money to finish the "Loser" video and re-released the single. It blew the fuck up. "Loser" topped the Modern Rock chart before Geffen had time to release Beck's Mellow Gold album, which he recorded on his own before signing. Thanks in part to heavy MTV play, "Loser" also crossed over to pop radio. The single climbed the Hot 100, eventually reaching #10 and going gold when that actually meant selling physical singles. "Loser" is still Beck's biggest hit, mainstream or otherwise. On the 1994 Pazz & Jop poll, critics voted "Loser" the #1 single of the year in an absolute landslide. It had nearly twice as many points as the #2 song, Veruca Salt's "Seether." (On the Modern Rock chart, "Seether" peaked at #8. It's a 9.) Beck was great on TV, partly because he was so uninterested in being on TV. I have fond memories of Space Ghost introducing him as "guitarist-slash-musician Beck." Also, Beck was 24 when "Loser" blew up, and he looked like he was about half that age. He still looks like he's about half that age.

Beck wasn't especially psyched to see "Loser" go supernova. Later on, he told Pitchfork, "It's like if a friend took a stupid picture of you at a party on their phone, and the next thing you knew, it was on every billboard." When he put a band together and started playing live, he'd often pull the classic '90s alt-rock move of refusing to play his one big hit. (Radiohead, who had a similar experience with their own self-deprecating 1992 smash "Creep," could relate. "Creep," by the way, peaked at #2, and it's a 10.) "Weird Al" Yankovic wanted to make a "Loser" parody called "Schmoozer," which could've been fun even if "Loser" is already effectively a parody of itself. Beck didn't give permission, though he later regretted it. He also wasn't OK with the idea of "Loser" appearing on the Dumb & Dumber soundtrack. He made a lot of decisions that really don't help me when I'm putting together the Bonus Beats section for this column. Even then, though, Beck didn't seem tortured by his own out-of-nowhere success, the way so many of his peers were. At worst, he was merely aggravated.

Beck's Mellow Gold album came out on Geffen in March 1994. "Loser" is the first track on the LP, as if Beck just wanted to get it over with. Track two was "Pay No Mind," the one where Beck rhymes "I sleep in slime" with "I just got signed." The rest of the album is full of gurgling, lo-fi experiments, some of which have seemingly accidental hooks to rival the one on "Loser." Mellow Gold is among the most skronky and disheveled major-label albums from an era when major labels were getting used to the idea of releasing skronky and disheveled albums. Critics loved the record, putting it at #10 on the Pazz & Jop poll -- just behind Nine Inch Nails' The Downward Spiral, just ahead of Soundgarden's Superunknown. Initially, the sales climbed high through the garbage-pail sky like a giant dildo crushing the sun. One million Americans bought Mellow Gold on compact disc. I was one of them.

Judging by what I saw in the ensuing years, at least 750,000 Americans must've then sold their copies Mellow Gold back to used-record stores. I saw that thing all the time when I was flipping through bins. I was not among the sellers, but I definitely thought about it. I knew that "Loser" was good-weird. It took some time to decide whether the rest of Mellow Gold was good-weird or bad-weird. I eventually landed on good-weird, partly because it was fun to make my voice all deep and sing "Truckdrivin Neighbors Downstairs" directly into the bottom of a bongo drum, hearing my voice echo -- the same impulse, I'm guessing, that led Beck to make "Truckdrivin Neighbors Downstairs" in the first place. I was also into the catchy, uptempo tracks like "Beercan." That one sounded like a hit, but it never became one. On the Modern Rock chart, "Beercan" topped out at #27, and no other Mellow Gold tracks charted.

In his Geffen contract, Beck had a clause saying that he could release weirder music on indie labels if he wanted, and he took advantage. Three different Beck albums came out in 1994. Stereopathetic Soulmanure is a collection of studio fuck-arounds even more intentionally off-putting than the ones on Mellow Gold. The punk label Flipside actually released that one a week before Mellow Gold came out. A few months later, K Records put out One Foot In The Grave, a lo-fi acoustic record that Beck made with Beat Happening frontman and K Records boss Calvin Johnson, in Johnson's basement studio. Beck was not going to present himself as an alternative rock star, and you couldn't make him. Those other two albums were considered fun little curios at the time, but they both had songs that resonated down the line. A few years ago, Mike Powell wrote a great Pitchfork Sunday Review of Mellow Gold and pointed out that both of Beck's 1994 indie albums had songs that were covered by towering figures not long afterward. In 1996, Johnny Cash covered "Rowboat," from Stereopathetic Soulmanure, and Tom Petty covered "Asshole," from One Foot In The Grave. That's pretty good!

Beck came off as a readymade one-hit wonder, and he almost courted that designation. It set him apart. Beck might've been annoyed at what happened with "Loser," but he used it as an excuse to do weird shit on big stages. He hung out with Thurston Moore and joined Sonic Youth on the 1995 Lollapalooza tour -- the one where the bookers went all-in on weird indie stuff, which was not a smart financial decision at the time. That was my first Lollapalooza, and I mostly remember Beck looking nervous and tentative up there. That was better than his tourmates in Pavement, the other big act who always had the "slacker" label appended to them. Those guys were actively shitty, whereas Beck was perhaps at least trying not to be shitty. My Lollapalooza stop was the infamous West Virginia one where the crowd threw mud at Pavement until they went away. I dimly remember that incident, but I'd mostly stopped paying attention by the time the mud really got to flying. (Pavement's only Modern Rock hit, 1994's "Cut Your Hair," peaked at #10. It's an 8, and it's one of the only Pavement songs that I like. Later on, Beck produced a Stephen Malkmus solo album.)

Beck wasn't exactly sprinting back toward the zeitgeist, but "Loser" had a huge effect on alt-rock radio for the next few years. In the second half of the '90s, we got so many tracks with white guys half-rapping arty, surreal nothings over dusty breakbeats. It was practically a genre unto itself. Maybe this was the alt-rockers' best attempt to engage directly with rap music -- with distance and irony as armor, trying to stay cool by acting like they didn't care enough to be cool. A good handful of those songs will appear in this column. Some were good, and some were not. Beck didn't associate with those acts, and he didn't chase hits. Instead, he pulled off something more impressive.

Everyone was pretty surprised when Beck got his shit together in a big way. Beck went to work with the Dust Brothers, the LA producers who'd helped the Beastie Boys assemble their 1989 sample-collage masterpiece Paul's Boutique, and he made moterfucking Odelay. That album took "Loser" as its starting point, capturing all of that song's loopy sideways energy and none of the scabby experimentalism of Beck's early records. Odelay sounded homemade but streamlined, alien but familiar. It was smart and fun at a time when people struggled with either side of that equation, and it solidified Beck. Odelay sold two million copies, making it Beck's most popular album. It easily secured the #1 spot on the Pazz & Jop poll, trouncing the Fugees' runner-up entry The Score. Odelay also scored Beck his first Album Of The Year nomination at the Grammys; he lost it to Céline Dion's Falling Into You.

Odelay didn't have a radio hit on the level of "Loser," but a bunch of its songs went into rotation. Lead single "Where It's At" sounded a bit like Beck was trying to make a novelty hit, and that one reached #5 on the Modern Rock chart. (It's a 7.) Four different Odelay singles made it onto the Modern Rock chart, and another one went top-10. ("New Pollution" peaked at #9. It's an 8.) In 1997, I saw Beck headline the HFStival, my local alt station's annual stadium show, and he did not look like the same guy who came off smaller-than-life at Lollapalooza two years earlier. He was a consummate professional, a funky showman who was breathlessly entertaining even when his act seemed like a meta-commentary on funky-showman archetypes.

Odelay pretty much turned Beck into a music-business insider, which nobody could've seen coming in the "Loser" days. The industry wanted to present itself as a venue for arch sophistication, and Beck had tons of that. Beck followed Odelay with album-length statements that earned critical raves without getting much alt-rock airplay. Radio was moving away from Beck, and he didn't seem to mind that one bit, since he still had license to do whatever he wanted. He followed Odelay with 1998's Mutations, a downbeat acoustic record that he made with Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich. It's probably my favorite of Beck's periodic downbeat acoustic records, and it didn't get any radio play. (Lead single "Tropicalia" peaked at #39; none of the other songs charted.)

After Mutations, Beck took a hard swing back into the funky-showman lane. 1999's Midnite Vultures is probably still my favorite Beck album -- a delirious plasticity party that celebrates and exaggerates the erotic-city landscapes conjured by Black geniuses like Prince. (A couple of Midnite Vultures singles cracked the Modern Rock chart; "Sexx Laws," the bigger of them, peaked at #27.) Midnite Vultures got another Album Of The Year nomination, and Beck followed it with his heart-crushed acoustic breakup album Sea Change. That one didn't get radio play, either. ("Lost Cause" peaked at #38.) Honestly, I don't really care about whether alt-rock radio was playing those Beck records because I know those Beck records kick ass. It's such a pleasure to use this space to write about someone who made it out of the '90s just fine and who kept experimenting and coming up with different ideas over the years. I love my tragic heroes just as much as anyone, but it feels good to see someone win for once.

Even without a significant radio presence, Mutations, Midnite Vultures, and Sea Change all went gold. Beck was doing just fine in his critics'-favorite lane. But then something funny happened: Beck and alt-rock radio found themselves moving toward a convergence point in the early '00s. Maybe it just wasn't a time of chimpanzees anymore. We'll see Beck in this column again.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: In mid-'90s ECW, there was a wrestler named Mikey Whipwreck, a permanent-underdog little guy who didn't look like he could beat up anyone. Mikey's whole thing was that he had no business in a wrestling ring but, through sheer luck and determination, would sometimes win against terrifying monsters and then have to defend the championships that he couldn't believe he'd won. ECW didn't pay any attention to little things like clearing the music that they used, so Mikey naturally entered the ring to "Loser." Now that WWE owns the entire ECW tape archive, it's hard to find videos of Mikey coming to the ring to "Loser," since the bigger company just dubs over all the uncleared entrance songs with generic rock music, but here's a Mikey highlight reel that someone set to "Loser":

THE 10S: Björk's honking epicurean house banger "Big Time Sensuality," the closest that she ever got to sounding like Crystal Waters, peaked at #5 behind "Loser." It doesn't necessarily take courage to enjoy it, though I'm sure that doesn't hurt. It's a 10.