Steve Hartlett on learning to rock at Connecticut DIY shows and his cult-beloved rock group's new album Buds

Steve Hartlett is very disappointed to hear that I broke my foot at his gig. I am speaking with the Ovlov frontman after a cancelled visit to his New Haven home and half a week of phone tag, discussing the band's first show back -- and also mine --at The Broadway in Brooklyn in early August. He laughs upon being reminded that at one point that night he played guitar with a dustbin: "I'm so anxious leading up to and while we’re playing that it’s a bit of a blur." But he takes on a more concerned tone upon hearing about my injury. "People were going a little too crazy," Hartlett says with a sigh. "I was very concerned that someone would get hurt and apparently I was right."

On the other hand, a raging crowd at an Ovlov show is to be expected because people tend to get pretty excited about this band. Hartlett has devoted his entire life to music. He has a solo project called Stove, he plays in longtime collaborator Jordyn Blakely's band Smile Machine from time to time, he releases some music under just his full name (most recently September's Waste Of Water), and there are probably other vessels through which engages in music making or playing. But Ovlov -- whose lineup is currently Hartlett on vocals and guitar, his brothers Theo on drums and Jon on bass, and Morgan Luzzi on guitar -- is his longest-running, best-loved project.

Despite a couple of breakups here and there, Ovlov have been around for a little over a decade and have amassed a cult following through both DIY shows and the Spotify algorithm. Their hit "Where’s My Dini?" off their 2013 debut full-length Am is the starting point for most; either that, or anything from their last record, 2018’s TRU. It doesn’t matter much where a listener starts with Ovlov -- their music, for the most part, has retained a distinctive fast, fuzzy sound in line with indie and alternative staples like Dinosaur Jr., Built To Spill, and early Foo Fighters. It has been consistently great, too, which has won them deep respect among their peers in New England indie rock.

"Steve has a sense of melody that almost feels classical, like a song you can't believe didn't exist before he wrote it," writes Sadie Dupuis of Speedy Ortiz and Sad13, who was based out of Massachusetts when Ovlov were getting their start in nearby Connecticut. It's an insightful read on Hartlett, who tells me he thinks of himself like a classical composer. Dupuis has been playing alongside Ovlov since the beginning, and she's sung vocals on some of their songs. "He knows how to find the notes and inflections that will make the line or the chord special and powerful," Dupuis continues. "It doesn't hurt that he's one of the greatest guitarists I've ever seen. Ovlov have been the biggest band in the world to me since around 2009 and I'm glad everyone else is catching up."

Greg Horbal, a booking agent and a former member of another Connecticut-founded group, The World Is A Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid To Die, booked Ovlov's tours during their early years. He describes the experience of hearing Am for the first time on the way to a show at Bard College with a bandmate. "I was driving through the woods, it was super foggy, and the sun was setting," Horbal remembers. "[Ovlov’s early EP] What’s So Great About This City? was not polished -- that's the wrong way to put it -- but Am was nasty. It was fucking blown-out; the sound was massive. It was the exact thing I wanted to hear from that band at that time. It was great. The entire LP was flawless. I was like, 'Whoa.' I really thought that they were going to be massive because the record was just so stunning."

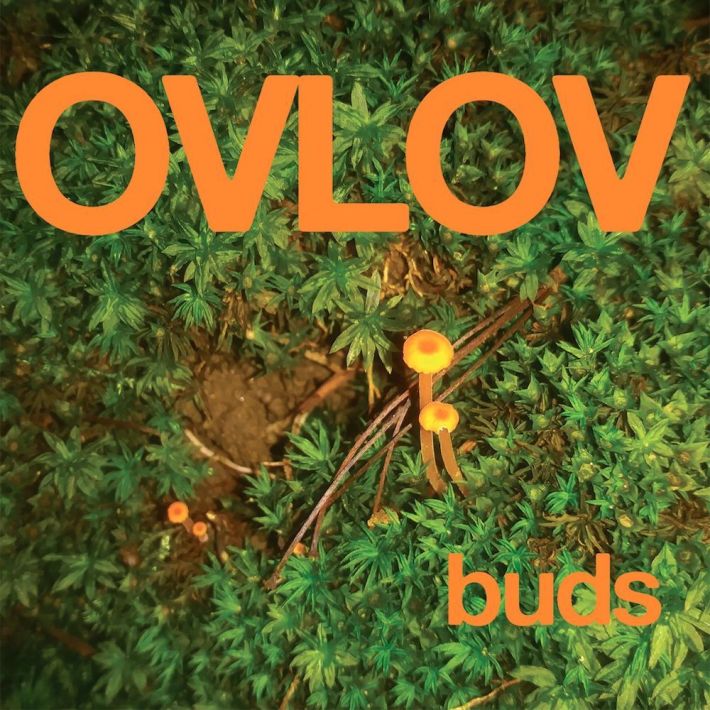

On Buds, the new Ovlov album dropping in November, the band has managed to make their music sound even more colossal. As heard on lead single "Land Of Steve-O," the eight songs on Buds are both explosive and intimate, constantly fluctuating from quiet, endearing moments to blaring, cathartic climaxes. Hartlett's words are spoken like secrets, and there's often a wisdom or two tucked into them: "Don't take gold from strangers/ 'Cause in the end you’ll see/ It will melt right through your fingers/ And you’ll never be," he intones on "Cheer Up, Chihiro!" Every track has a lot going on; each listen reveals a new surprise.

Today Ovlov are sharing a second advance track from the album, "The Wishing Well." Hartlett says it's about "how much I dislike the way some people respond to something a person with mental health issues might have done wrong, whether it be cops, all the way to the employees at your favorite 'DIY' venue in Brooklyn, NY." Below, hear "The Wishing Well" and read my conversation with Hartlett about Buds, his songwriting process, and the Newtown music scene.

Were you guys broken up during the pandemic? Or was that before?

STEVE HARTLETT: See, that was something we hadn't really figured out completely before the pandemic started. The last show we played before the pandemic was in July of 2019 and we considered that to be our last show in ways. Not permanently -- we just wanted to at the very least take a break from shows or just even the band in general, but we were also trying to figure out if we should just stick to writing and recording and releasing music and never playing live again.

We recorded the album that week before quarantine started. Quarantine itself put a lot of things into perspective in that it made me realize that I don’t hate playing shows as much as I thought because I did miss that a lot [laughs]. I only got to play like three solo shows after I quit drinking, which to me felt like my first three shows ever because for every other show I'd played I'd at least drank a little bit or got wasted beforehand, so it was just a totally new thing for me. I didn't really get to get used to that. I still haven't really gotten used to it; it just feels very, very different. Way too self-aware. I was able to at least not look at the crowd and pretend like they weren't there for a little bit when I was drunk, but it's not possible with weed. I’m too aware of my surroundings.

It's complicated because every time I have some time away from playing shows, I always start to miss them. Then inevitably the day of whatever show, I feel like I shouldn't have done it the whole day. I'm still trying to figure this out -- what I truly want to do with music in general, but the music I write more specifically. I feel like the most satisfaction I get out of playing music is really just writing and recording it, and once that's done I really just want to move on to the next thing. I just get sick of my songs too quickly so to have to play them more than once is frustrating let alone hundreds of times.

I'm right in the middle of trying to figure out what I actually want to do with music. I know I like playing shows, just when it comes to performing songs that I wrote specifically, and when I'm the one singing and I guess leading the band, it becomes a different thing that feels like something I don’t enjoy. But when I play drums with Smile Machine or playing anyone else's band or even if we were playing covers with Ovlov, it just feels different from when I'm performing songs I wrote for some reason. I almost wish it were possible for me to just write the songs and have other people perform them entirely [laughs]. Like what classical composers do. They pretty much just write the music down and then other conductors and symphonies perform it and they just sit back at home and keep working on stuff without having to leave their room [laughs] That’s just a joke because I don't like to leave my room much.

Well, that makes sense because I think what people appreciate most about you is that you're an amazing songwriter.

HARTLETT: Thank you, that’s really nice.

But I do feel like your songs are written in a way that’s meant to be heard live.

HARTLETT: Yeah, with Ovlov specifically, too, I would say so because of the intentions behind the sound of the band in general when we first started it. And I haven't really changed those intentions too much as far as the style of the songs. I don't know, I really shot myself in the foot there.

I do think it's crazy that your music has been consistent for so long. How would you describe those "intentions" for the sound of Ovlov?

HARTLETT: I guess, as simply as I could put it -- because I feel like it is in my mind rather simple anyway -- I've always liked really pretty music, and I've always liked really heavy music, and I just felt like it'd be nice to have a band where it's like… I don't know, I guess originally I was thinking the Deftones without screaming but faster drums. Deftones with a punk rhythm but not quite as gothic. Does that make sense? [laughs]

Deftones do not come to mind when I think of Ovlov so that's really interesting.

HARTLETT: Yeah... Their music isn't as much of an influence as it's really just the way he sings over such heavy music. I really think it’s a cool contrast. They weren’t the first band to do that, they were just the first band in my life like that.

Do you have any rules for what makes a good song? Do you think there's a logic to it?

HARTLETT: I definitely used to think there was a more specific definition and fact of what makes a good song a good song, but I'm just constantly surprised. I can really only use my own songs as a basis for this judgment I've been making. As an example, the two songs that are the most popular on our first full-length Am, "Where’s My Dini?" and "The Well," are the only two songs I was considering not putting on the album because I just didn't like them and I didn't think people would like them as much, and they turned out to be the most popular. I can never predict what songs of mine people are going to like or they're not going to like just because of that specific album and that decision to actually put them on there. It also got me into recording everything I write whether or not I like it because there's always a chance of that happening again.

I'm not quite sure any of our songs have ever been as popular as "Where’s My Dini?" in particular. We may just be remembered as… I can't even say one hit wonder because it was never quite a hit [laughs]. But whatever, that's fine. I love a lot of one hit wonders. I would be honored to be considered anything at all let alone talked about in the future. Anyway, I don't know what the hell I'm talking about sometimes. Did I even answer the question? No, I didn't. Okay, so I guess there is definitely an educated, specific explanation of what makes a song a good song. I wouldn't be able to explain it or possibly even agree with it because it just seems like it's so subjective.

Which Ovlov song do you think is your best?

HARTLETT: Now, are we talking my favorite song or the one that I think is just factually the best song as far as what I was just talking about, like what a college professor who teaches music theory might say is our best song because of these points?

I’d like to hear both answers.

HARTLETT: It might be the same song. I think our best song and my favorite song is "Short Morgan" on TRU. I don't know why, it's just kind of… Yeah, like I could not tell you why. It's the most fun to play. It doesn't feel like a song I actually wrote, it feels like one that just kind of happened, and I wasn't trying to sound like anyone specifically. Though I know it does sound like many people specifically.

Who do you think it sounds like?

HARTLETT: If I were writing for Vice or something I would say I feel like it sounds like Lemonheads or Dinosaur Jr, just easy, quick comparisons, which it does. It's not like they'd be wrong, this fictional Vice writer. I think that's partially why I like it as much as I do because Lemonheads in particular are one of my favorites.

How do you write your lyrics? They're very coded and conversational.

HARTLETT: They definitely all have some sort of deeper meaning to me, whether or not I'm totally aware of it as I’m writing it. I try to make them vague so that people can tell they are about something and attach their own meaning to it because that's essentially what I do with other people's music that I love -- it's only what I think it's about. I've never gotten to ask these people directly, so I almost don't want to know sometimes. I feel like when I find out what a song is truly about sometimes I get disappointed so I'd rather someone just think what they want to think it's about. Unless it's some really bad shit, then I'd love to correct them. But I think it's pretty obvious they're just mostly about first world problems [laughs].

I talked to Neil Berthier [of Donovan Wolfington and PHONY] the other day and told him about how I'm interviewing you, and he just started talking about growing up with you guys. He said that everyone who lived in your town wanted to be as good as the Hartlett brothers but could never be so they just did something different. I thought that was really interesting. I was wondering if you could speak on that.

HARTLETT: Oh, man, that's a really sweet thing to hear. It's also kind of funny to me, because I feel like everyone in Newtown did the same thing. We all had a ska-punk band, and then we all had some emo rock band with a synth in it probably, and then we dropped the synth and got Big Muffs, and here we are today. I don't know. I'm just fucking around. That means a lot to hear; I just have trouble hearing compliments, and I have to deflect them with stupid jokes. But it's partly true, too. We were all doing the same thing. We all just liked Rancid and watched fucking Jackass on TV. We were shitheads. [laughs] Do you want me to say something nicer than that?

What was it like being in that scene?

HARTLETT: I feel really, truly lucky to have grown up in Newtown for the music scene. It's weird to say to even people in Connecticut, just anyone outside of Newtown really. I think if I had even grown up in a town over like Southbury, I wouldn't have gotten to experience the things that I got to because of how many bands came from Newtown, but also just how many bands played at our teen center like once a week. In middle school and high school, I would pretty much go to or play a show at least once a week at the teen center in Newtown. I feel like it was this little training ground for us to learn how to be a band and play shows. It was a really lucky place to be. My best friend's older brother was about five or six years older than us, but he was in a popular hardcore punk band when we were in middle school, and we were just looking up to him and growing up getting to watch his band play with all these other bands. It was a very special thing that I feel like a lot of other towns had but didn't have as much of. Maybe it's just because I'm from Newtown, but I could name at least like 30 bands from Newtown, but I could maybe only name like one or two from the surrounding towns in Connecticut.

This was really just when I was in middle school and high school, and for some reason a lot changed after that. They stopped allowing shows at the teen center, and I don't know what it was. My younger brother Theo and Neil are in the same grade and they've known each other since elementary school. After their year graduated and went to college, I feel like there weren't really many bands, at least that I know of, younger than them. So I feel like that scene has kind of fizzled out in a way.

How old were you when you started playing music?

HARTLETT: I got my first guitar when I was eight. I pretty much started writing songs as soon as I got home with the guitar. My dad's uncle gave me my first guitar. I didn't know how to play obviously; I was just mocking what I'd seen my dad and other people do. But even before I could play guitar, that's all I wanted to do was just write songs. I don't think I actually had a band till I was probably 12 or 13. It wasn't like a band-band. It was just my friends who I played a few songs with. I think we played a show at my church once [laughs].

Your dad is a musician?

HARTLETT: Yeah. His father -- my grandfather -- was also a very admirable musician. He didn't really write, but he was constantly performing live by himself or with other people. My dad as well. He played music his entire life and wrote music. He's definitely what got me wanting to write songs because when I was like seven or so, he was starting to tell me stories about his past bands, and just knowing he did it made it all seem possible for me to so I think that's all I ever really wanted to do. So it's now unfortunately all I'm really good at doing. I wish I learned how to do something else [laughs]. I'm just joking. I’m very lucky to have my father and his father be people that are very musically inclined and passionate about it.

What kind of music does your dad make?

In the late '70s and early '80s, he was in a band called Fast Fingers and they just did covers mostly. I think towards the end of their career in like 1980, they wrote and released four or five songs. Those were the kind of rock music you'd hear on the radio at that time. Just pop-rock, I don't know what to compare it to really. It's all on YouTube I think. Maybe not. Either way, it's great. I have their record on my wall, a 7" 45. Some point in the '80s, he got sober and became a born-again Christian and he just wrote like Christian rock songs [laughs]. That’s what I at least growing up saw him doing as far as songwriting goes. But in a way I definitely feel like those songs -- maybe not his songs in particular, but the songs we had to learn how to play and sing in church -- kind of helped me learn how to write and structure songs. I feel like at least 90% of my songs are structured like Christian worship songs in that they're just like intro, verse, chorus, intro, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus. Most of my songs follow that formula and it's not just me. Rancid does it a lot [laughs].

What does your dad think of your music?

HARTLETT: He is maybe one of the strongest supporters of my music and always has been. He's always been very open to listening to anything I've ever shown him of mine or that I liked just my whole life. He'll be honest and critical about whatever he hears but never in a judgmental way. He'll just ask, like, why do I like what I’m showing him? Or why did I choose to do something in my own songs that he may not have done himself or didn't like himself? But he never considered it to be wrong or bad. What I appreciated and learned from both him and my grandpa was that just because you don't like something doesn't mean it's bad, especially if it's new and different. There's nothing to base that judgment off of really.

You were talking about earlier how you get tired of your songs pretty quickly, so I'm wondering if you're kind of tired of the songs from the new album yet since it's been a while since you made them.

HARTLETT: Yeah, unfortunately I'm quite sick of them. Some of them not so much as the others. I still like them, and we haven't played them live much at all. Some of the songs, like "Land Of Steve-O" and "Eat More," were songs that I wrote and demoed out before TRU even came out. I just felt like they were too poppy for TRU, so we kind of just sat on them. That was like 2016 when I was writing this stuff for TRU and Favorite Friend, the Stove album. I think a few other of those songs on the album were from that time period. 2016 is the year my best friend passed away, and I just wrote a shitload of music after that. I think most of the stuff on TRU is from that year, I think most, if not all, of Favorite Friend is from that year. But yeah, both the Stove EPs were just the demos that we did that year that we decided we weren’t ever going to re-record again.

So everything that I demoed for TRU and Favorite Friend was all with my friend Alex Molini who played bass for Stove for a while after that. It was in his room in Brooklyn that we demoed all this shit and then decided what to do with it after the fact. Some of it was for Ovlov, some of it was for Stove, some of it was for we don't know what yet. I guess a lot of the songs on the album are from that. But some of them are only from a couple years ago, maybe even less than that. They’re all old. But I haven't gotten to the actually perform them enough to actually get sick of them. And that feeling also goes away. If I just take a break from whatever I'm feeling like I'm starting to get sick of, then it doesn't take long for me to want to play them again.

Did you have any goals going into making the record?

HARTLETT: Yeah. To be totally honest, I would love for one of those songs to be used as a theme song for some TV show just so I can have some consistent income. That's only partly a joke. I definitely feel like this album is a bit poppier than anything else we've released. Hoping that pays off literally and figuratively [laughs].

Did you try to make it poppier?

HARTLETT: Yeah, for sure. I've just always loved pop music. I always felt like Ovlov was pretty poppy in general. Everything can always be poppier in my opinion. I don’t know. I just wanted this one to be different than the first two. There's definitely some songs on there that don't sound like Ovlov songs to me, but we made them that way. We made them sound as Ovlov as possible.

Which songs?

HARTLETT: In particular, I feel like "Land Of Steve-O" is rather poppy for Ovlov. "The Wishing Well" I feel like is a bit out of our realm. "Strokes." "Cheer Up, Chihiro!" is a song we've been playing for almost 10 years now but are just now releasing because I've always felt like that one was too poppy. I love playing it. It's one of my favorite songs to play. It’s just always felt it was too poppy for us to put on an album, but I felt like this one was worth taking a risk for. It's our third album, we've been a band for fucking over a decade. I’m surprised people still listen to us and care about us at all let alone are excited to hear this. It's really something I never would have imagined and I'm very grateful for.

People are still just now finding out about you guys.

HARTLETT: Yeah. I kind of felt like after Am happened like that was the biggest we'd get. Then we released TRU and got this whole new wave of fans from it, and it was really cool to see. I'm hoping that happens with this one, but even if things stay the same they're still pretty good so it's a win-win.

And I feel like your fans are constantly pressuring you to put out new music. I see your Instagram comments and before this record was announced no matter what you posted people would be like, "So where's the new record?"

HARTLETT: I know! I'm always saying, "Soon! It's happening!" That can also be a bit frustrating because I release a lot of other music under other names and it pretty much sounds the same. Just because it's not called Ovlov doesn't mean it's not basically Ovlov.

How do those expectations affect how you make music, if at all?

HARTLETT: They definitely do. I wish they didn’t. I've heard comedians say this more than I've heard musicians, that once they tell a joke it's out there and it's the world's joke. It's no longer theirs. And I kind of feel that way about songs too. So now that I've invited these people in to hear mine, I feel like I owe it to them in a way because I also hope for that from all the artists I love, whether it be visual artists, any art form really. It's really, truly special to have someone care about something you create, and that alone becomes enough inspiration. As much as I'm definitely always just doing it for myself, at the end of the day it's nice to have people care and actually want to hear it. It definitely makes it easier to want to make it myself.

Can you tell me about the lineup change?

HARTLETT: My older brother played bass for Ovlov for the first four or five years that we were a band. He played on Am. I think pretty soon after Am was released, Boner [Michael Hammond, Jr.] started playing bass. We got asked to play in that show in July in 2019 that was our last show before quarantine happened, and since we decided it was gonna be like our last show for a while it was at the Newtown teen center. It was one of my best friend’s pre-wedding parties. He met his now-wife at the teen center at one of the shows that we were playing in high school, and so they thought it'd be fun to book a show at the teen center the night before their wedding given they met there and everything. We felt like it would be extra special to have my older brother Jon play bass with us again for that show.

That show happened, we took I don't know how much time before we decided we were gonna record a third album, and after that show happened we just thought it'd be cool to have my brother play bass on this one again. Also, I just felt like these songs were a bit more like my high school band, which was a bit more poppy, that my older brother played bass in. His bass parts in particular felt essential to those songs. I also obviously feel that way about all those bass parts on Am. They are some of the most memorable parts of the songs for me, and I just really wanted to have him write the bass parts for these songs in particular because I knew he would really add something special to them.

I think every release has had a different lineup on it. It's ever changing. Mostly just because I'm constantly changing my mind about what I want to do with my life and most of my life is around this band. Luckily I have a lot of flexible people around me [laughs].

Where did the title Buds came from?

HARTLETT: It kind of starts with how we decided to name Am. "Am" was like this inside joke between my two brothers and I and our cousin Milo. I can't really explain why it was funny or what the joke even is but we just would say "Am" as a response to a lot of questions like, "How are you?" "Where are you?" You would just say "Am," it’d mean, like, "I'm good." I don't know. Again, I'm not going to try to explain this too deeply because I don't think any of us really could explain why it was funny anyway. "Am" was just a word we were saying a lot, and then TRU came around. The time to release TRU was like five years after that, and "TRU" was just a word that we were saying a lot at the time. Really not much thought goes into naming anything. The band is just "Volvo" backwards.

For Buds, we made a group chat to decide what to name it, given the first two albums were named just based off of things we were saying a lot because we were hanging out a lot and we all haven't really seen each other for a long time or been talking nearly as much as we were because of the pandemic. We decided we wanted to keep it one word, like the first two albums. And "Am" was a two letter word, "TRU" is a three letter word, so we wanted to think of a four-letter word for this one. Also, if we could make it sound like a sentence, so the three albums in a row would be good. So "Am TRU Buds." It's three brothers and one of our longest childhood friends, Morgan. So many of the songs are about friendship, just close relationships in general. We assumed everyone would just assume that it was a weed reference, which it can be. It can be whatever. It's not something that took much thought but it is meaningful in ways.

That's what I mean when I say that the lyrics are coded. Even the band name and the album titles are inside jokes.

HARTLETT: Yeah. There's definitely some intent behind all that vagueness.

Buds is out 11/19 on Exploding In Sound.