The Ramones Albums From Worst To Best

If everyone who ever bought a Ramones shirt bought a Ramones album, they’d be as big as fucking Aerosmith by now. But then, how many Aerosmith shirts do you see at shows? The glamour of cultdom was lost on the Ramones; they didn’t care about the margins. They wanted to be your Beatles. And in some slightly altered reality, they might have been. They had hooks tumbling out the legs of their jeans; a cartoony, all-for-one/one-for-all image; and a dogged work ethic that endured disastrous bills, lineup changes, and intra-band feuds. Even when it was clear that the radio had no place for them, they never broke kayfabe, delighting pinheads the world over to the tune of 2,263 shows: impressive for any band, staggering for a punk act. The Ramones took their place in pop history seriously, even if they didn’t always know what it was exactly. Weaned on glam rock and girl groups, Stooges and Stones, these knuckleheads concocted a throwback sound that was shockingly novel. They played rock and roll at twice the speed — stripping out the solos and the soul — in service of trash culture and real life.

It took a little convincing from Tommy Ramone (justly lauded in obituaries as the band’s architect), but the boys quickly went from flailing Forest Hills fuckarounds to punks with an eye on world domination. Previously taken by the glitter boom, they cannily swapped their lamé boots and velvet jackets for Perfecto leather jackets, tennis shoes, and cheapo pop culture tees, figuring that the kids in Middle America would find it easier to emulate them. Tommy’s 1975 one-sheet for the band touted their stock of would-be hits; they hadn’t even started recording the album. But they’d already arrived at their sound: punchy, streamlined rock and roll, with naggingly repetitive passages where the solos could’ve gone. Dee Dee thumbed along the chord changes; Johnny merged an au courant heavy tone with a speedhead’s sense of time, playing like he was paid by the downstroke; Tommy began waging a years-long campaign against fills of any kind. And Joey — gangly, jumpy Joey — was a frontman practically without precedent. His timbre was like a bottle of milk left to curdle on a suburban sidewalk, vibrato-free and clipped, an unmistakable Long Islander with a Brit inflection. Tough and tender, he embodied the romantic delinquent, whether he was courting or turning tricks.

When the Ramones started their run at CBGB, witnesses weren’t sure what they were either. What to do with four Long Islanders, outfitted in matching ripped denim, leather jackets and pageboy-gone-to-seed haircuts, tearing through twenty songs in as many minutes? Some believed they were seeing something closer to comedy than music; others, like the Talking Heads’ Chris Frantz, fervently believed the Ramones were art-rockers, like La Monte Young blasting the Nuggets box with only a bag of glue for company. Like everything, they had their precedents. There were the Stooges (Ramones minus charm), the Dictators (Ramones minus concision), the New York Dolls (Ramones minus tunes). There were hundreds of garage acts, yearning to smear a little post-pubescent angst on the Top 40 form; some of them succeeded.

The Ramones didn’t. Not by their pie-eyed standards, anyway; punk rock, with its circumscribed tier of success, didn’t exist when they strolled into Tom Erdelyi’s studio. Forget the art-school noodlers who they were supposedly set against. Their eyes were on Mick and Keith, the Who, the Bay City Rollers, the Beatles — if they made it, why couldn’t the Ramones? The Beatles in particular were an inspiration: the unified stage image, the airtight compositions, the count-in. The Ramones’ first LP even put the bass in one channel, the guitar in the other. And like the Beatles, the Ramones were top-notch songwriters, capable, in bursts, of melodicism and humor and punch every bit the equal as their idols. (Actually, “idols” may be pushing it; Johnny brought a bag of rocks to chuck at the Beatles during their legendary Shea Stadium concert, but they were parked on second base, and he settled for watching the show.) No one walked the line between smartass and dumbass better than these guys.

The Ramones’ genius was their willfulness. They loaded LPs with stormtrooper playacting, druggy excursions, and doofy love songs. They slagged Commies and Reagan; they wrote songs about Freaks and Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Tipper Gore. At some point, it must have occurred to someone that songs about glue and sedation and roofies weren’t going to rock the charts, but they kept plugging away, hoping that radio would meet the Ramones halfway. It never did, of course, but the band’s punk-pop formula was an international language, spawning global. Crass are godheads, and they never inspired multiple bands to cover their studio albums in full. The Ramones’ purported influence on the nascent British punk scene is probably overstated (a lot of key acts had already formed), but as four guys who decided to pick up instruments and kick the world’s ass, they were a walking gauntlet. The Damned and the Stranglers caught onto their mordant humor, Joy Division (I can’t prove this, but still) picked up on Tommy’s approach to the drums, the Buzzcocks churned out lovesick anthems to rival their peers’. Anyone plowing pop-punk soil in the last forty years is walking the Ramones’ ground.

Time was kind to the band’s popularity but merciless on their relevance; their reputation was made on their first four records (recorded within an astounding 28-month span), but there was at least one world-beater on the next five. As early as 1984, they were talking in interviews about giving the fans that classic Ramones sound, which Johnny assumed was heavy guitars played fast. There was so much more, of course. There were Dee Dee’s allusive, confrontational texts. There was an ace sense of dynamics, an almost-pat movement from verse to chorus to bridge. And there was Joey, a giant wounded sneer on the mic, punk’s great bleeding heart, geek and sex symbol both. There was also the supporting cast: Marky Ramone, the longest-tenured drummer; C.J. Ramone, the anti-Newsted, who recharged the band’s battery for a few more years; Danny Fields and Monte Melnick, the indulgent, shrewd managers; and Arturo Vega, the truest believer, the man who created the band’s logo, provided their stage lighting, and phrased their appeal in mystical terms.

You know the drill: these are the Ramones’ studio albums, ranked in order of preference. Yours may differ — it almost certainly will, and it certainly should. To the end, the band was capable of shocking the system with an impeccable pop tune from Dee Dee or a delicious violation of taste (often from Dee Dee as well). Even as they turned their focus to the stage (where the hits and cash could be reliably found), they were still the Ramones, with all the attendant skill and humanity. Their cultists became conquerors, but their legacy wasn’t pop-punk or punk rock alone. Anyone who listens to nominal trash and discovers the truth inside is a worthy inheritor of the Ramones’ legacy.

Mondo Bizarro (1992)

Let's take a second to appreciate Johnny Ramone. His conservative bent -- culminating in the "God bless President Bush and God bless America" signoff in his Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame acceptance speech -- eventually tore a chunk out of his rep. Over time, everyone realized that all those leads were played by Walter Lure and Daniel Rey. Eventually, the party line tagged Johnny as the minder, signing off on rush-job records so they could go out and rack up the tour receipts. And yeah, Johnny's frugality spawned some legendary tales. It also put the Ramones firmly in the pantheon. By policing the fragile personalities of his bandmates -- insisting on night after night of tight sets crammed with fan favorites, always advocating a sped-up, stripped-down sound, recruiting C.J. Ramone for both his pliability and vitality -- he transitioned the band from heroes to legends. Year after year, the band was good for 100 sets of communal, joyous punk rock, spreading the Ramones gospel to England, Spain, Brazil, Japan and beyond. He was the band's own Paul McCartney, the savvy nudnik who willed the ship to stay afloat. Blondie called it quits in '82, Talking Heads followed nine years later. Television broke up, reformed, then went on hiatus before the Ramones packed it in. And, of course, a host of hardcore luminaries came and went.

Joey believed in the Ramones, too. But he yearned for connection; Johnny craved security. So night after night, these boys-no-longer donned the jackets and jeans and gave folks the show of a lifetime: chants and signs and classic cuts and the Pinhead. They'd chosen their costumes and pseudonyms in order to more easily conquer Middle America; now, it kept Weirdo America in thrall. Three years elapsed between Brain Drain and Mondo Bizarro; they filled the gap with a brutal touring schedule, introducing C.J. to every conceivable market. The desire for Ramones product was sated with reissues of the first four records, as well as a video collection. Hotshots like Eddie Vedder, Soundgarden and Metallica lined up to pay homage. Meanwhile, Dee Dee toiled in the background, a ghost of a ghostwriter.

So when they finally greeted the Nineties with the half-assed Mondo Bizarro, it didn't matter. There's hardly a worthwhile song on the set, despite the presence of old hand Ed Stasium. By now, the Ramones' sound was no longer frantic perfect-world pop. It was Joey, bellowing over buzzy hard rock. And still, Mondo couldn't fulfill even that easy promise: C.J. sings lead on two Dee Dee/Daniel Rey compositions: "Strength to Endure" and "Main Man." (The latter, tragically, does not refer to Lobo at all.) C.J. didn't suffer from his predecessor's inability to play bass and sing simultaneously, which is kind of a shame; when he's not rounding his vowels in tribute to Joey, he's a bar-band punk-rock crooner, straining to put his thin timbre over. But on the low-end, he's definitely an asset, allowing the band to include a drop-out passage in "Take It As It Comes" (a Doors cover, down to the quarter-scale haunted-house organ) and pay proper tribute to the British Invasion on "I Won't Let It Happen."

In more than one sense, the addition of C.J. was fan service, so what's the harm in a little lyrical pandering? A smarmy response to the PMRC that's seven years too late, "Censorshit" doesn't get any wittier than the title. The carnival-midway hardcore of "The Job That Ate My Brain" finds the boys pondering their ultimate horror: a 9-to-5. But the cheesiest dish is "It's Gonna Be Alright," "dedicated to our fans across the world." A Joey/Andy Shernoff joint, it's a check-in with the fan club, assuring us that "all is very well, C.J. is here." Also, "wild hair is back in style" and 1992 is "the year of the monkey, gonna be real funky." Longtime fans probably picked up the poignancy inherent in the line "it's gonna be that you're the only ones that understand." Album closer "Touring" expands on those promises, laying out the itinerary, assuring the listener that the road life's a gas. (What wall of silence?) The track is straight pastiche, a doofy mixture of "Sheena Is A Punk Rocker," "Rockaway Beach" -- which gets a namecheck -- and a dozen surf-pop hits. BGV heroes Flo & Eddie offer too-zippy whoops; they understood a put-on when they heard it. The Ramones tabbed Samuel Bayer to provide a Samuel Bayer video -- their one nod to modernity -- for Dee Dee's excellent AOR anthem "Poison Heart." The video stiffed. The next time the band hit the studio, it was to expand on the Doors cover, resulting in the K-Tel-worthy Acid Eaters.

Halfway To Sanity (1987)

The sanity of the title probably refers to the fiscal variety, as Johnny exchanged pop possibilities for dirt-cheap production work, courtesy of Daniel Rey. A Rey-recorded demo had made it into the band's care; impressed, they called him up. As a Ramones fanatic, Rey wasn't exactly about to push market rate for his services. He ended up an indispensable part in the Ramones machine, as important to their continued existence as C.J. Ramone would become. At this point, however, he was an affable presence who could quickly and professionally track some punk rock. The rest of the band seemed to pick up on this shift, if only subconsciously. Their gift for the arresting pure-pop single, discovered in the middle of their career, disappears as suddenly as it arrived. Joey offers up "Bye Bye Baby," a simpering Spector knockoff that limps to the finish line, its singer mumbling about 10 words while looking at his watch. It's a gloomy bit of regression, the kind of cynicism the band had resisted so fiercely.

Joey's songwriting slump continues, as he gets a mere three songwriting credits, all stashed on the back half of the record. "Death Of Me" is a numb depiction of co-dependence that insists on the resonance of the phrase "crazy carryin' on." It's like a piss-take on the Misfits. "A Real Cool Time" is much better. Harkening back to the first few albums in its melodicism, cheerfulness and the inclusion of a specific location (here, the Cat Club). Joey still has to work up to the refrain from the bottom of his range, though; it emotionally derails the song every time. Dee Dee's "Go Camaro Go" is its own little time capsule: it's loaded with the papa ooh mow mows from "Surfin' Bird" (covered on Rocket to Russia), it features old pal Debbie Harry on harmonies, and it boils the Jan & Dean ethos down to four words. The melody cycles relentlessly -- identical for the refrain and verses -- making this a sort of rock 'n' roll tone poem.

Daniel Rey, meanwhile, scores two co-writes on the front half, the only two songs to make Rhino's Loud, Fast Ramones compilation. "I Wanna Live" is a fever-dream revenge tale, fortified with BÖC-style arpeggiation and Johnny Marr chime, courtesy of Secret Fifth Ramone Walter Lure. "Garden Of Serenity" ends up as a loving homage to the Misfits. Ghosts and graveyards abound; Joey barks the title phrase like a cheesed-off dad, an eerie foreshadowing of Frank Costanza. Rey puts the toms up front, then quickly changes his mind. On "Worm Man," though, he goes all in on Richie, letting the kit eat up space, the better to cover up Joey's impression of a bloated Jim Morrison. Richie's handling of the broken meter on "Weasel Face" similarly distracts from his singer, but this time Joey elevates the crummy material with scratchy yells and nasal honks. The lyrical Sabbath homage "I'm Not Jesus" clarifies a confusion held by absolutely no one, but everyone capably navigates the hardcore passages, and they sound suitably demonic on the chorus. The mumbling priest is a bit much, but still: a capable composition from the drummer.

Halfway To Sanity runs for less than a half hour, the Ramones' shortest record since the debut. Hell, even the titles are shorter: for the first time, nothing exceeds four words. Even a dispirited Ramones record is worth listening to, but this is pushing it. One bright spot, though, is the reappearance of Dee Dee's vocal chaos; his songs may not be up to snuff, but one wonders what would've happened if his bandmates had written an entire LP around him. "I Lost My Mind" is his one lead, but he's expelling enough demons for 12 cuts. It could never have been, though; he went to hospital and emerged as Dee Dee King, trash rapper. He had given his band the best of his warped outlook, but that wasn't enough for either party. (According to Johnny, Dee Dee didn't even play bass on anything from Animal Boy through Brain Drain.) He stuck around for one more record, leaving before Alternative Nation made his band the most beloved legacy act of the era.

Acid Eaters (1994)

This record is equal parts retcon and concession. Would the Who record a covers album? Or Creedence? Maybe Joey's beloved bubblegum acts, but Acid Eaters posits a band that ate their Nuggets and grew up strong. Anyway, pulling Joey Levine to sing backup on "Yummy Yummy Yummy" wouldn't be as cool as tabbing Pete Townshend to bellow in the background of "Substitute," and thus is it here. American hero Traci Lord does the same on "Somebody To Love," and American frontman of Skid Row Sebastian Bach knocks off an item on his bucket list with the Stones' "Out of Time." It's mutual fanservice. And it's nice to see that in this late stage, the Ramones were comfortable enough with their legacy not to fret about notching an alternative rock hit.

Still, that didn't prevent them from sounding like an alterna-bar band, especially on C.J.'s three vocal features. Marky kicks up a towering cloud on the Joey-fronted "7 And 7 Is," swallowing his bandmates whole, showcasing the kind of freewheeling style in which he so rarely got to indulge. Johnny's playing is hit or miss -- he turns the chug of the Amboy Dukes' "Journey To The Center Of Your Mind" into an homage to the Batman theme, but his alley-cat squeals on "Can't Seem To Make You Mine" belong to a narrower imagination. Then again, Joey can't match Sky Saxon's louche dissipation, settling for a coquettish reading comprised of squeaks and dead-Elvis hamminess. To the amazement of all, his Long Island yawp is ideal for CCR's "Have You Ever Seen the Rain?," the most classically Ramones performance on the record. In another time, that honor might've gone to "Surf City," the closing track, but the tuff-guy BGVs are a world away from Jan & Dean's chippy sociopathy. Joey gifts the "two girls for every boy" line to Johnny's guitar, which is less an acknowledgement of sexism than a concession to limitations.

If anyone had earned a victory lap, it was the Ramones. In a couple of years, they'd hitch up with Lollapalooza, feted by -- and standing out against -- a host of alt-rock luminaries. The only video released from Acid Eaters, "Substitute," was a Cretin-Con all to itself, with cameos by Lemmy, White Zombie's Sean Yseult, Michael Berryman, and an intro from Lux Interior. But if you want to know what spawned the Ramones, you needn't look further than the first few records.

Subterranean Jungle (1983)

"After we made Subterranean Jungle, I was asked to leave the band," Marky told Michael Dawson of Modern Drummer. "I wasn't into drugs, but I was a periodic drinker." That period must've been geologic; how else can you explain the drum production? As a slavish imitation of electronic pads, it's phenomenal; as punk rock backbeat, it's puzzling. The so-wet-it's-scuba-qualified, ultra-low tuning is courtesy of Richie Cordell, songwriter for Tommy James and the legendary bubblegum label Super K Productions. The Ramones covered "Indian Giver," a song Cordell co-write for the 1910 Fruitgum Company, during these sessions, but three non-originals was enough for one record. If you're not Three Dog Night, three covers is a lot for a rock 'n' roll act, and the Ramones frontloaded the record with two of 'em. "Little Bit O' Soul" is a triumph of midrange, a clenched sphincter of quasi-gated riffage and scrapyard cowbell. Joey sounds really happy. "I Need Your Love" barely counts as a cover, as the original act (power-poppers the Boyfriends) never recorded it; the backing vocals positively swoon. The cymbals still lash like a thin leather strap, though.

Subterranean Jungle was held as a return to roots for the Ramones; the implication, I guess, is that nothing sounded like "Danny Says." The energy's here, but the tunes aren't. The self-references continue though: Joey singing "but they took her away," "Somebody Like Me" copping the "Blitzkrieg" chords. Johnny Ramone steps to the page with "Psycho Therapy," a throwback weer-all-crazee number that gives his singer free rein to ping sardonically across his range. The slowest cut, "My-My Kind Of A Girl," is Joey's, and it builds to a roar, like a garage band covering the Ronettes. But a garage band covering the Chambers Brothers? It's particularly sad that Marky, who cut his teeth as a teenage prog rocker, didn't get to flex across the breakdown in "Time Has Come Today," but drumming duties were handed to Billy Rogers of the Heartbreakers. "My soul has become… psy-ka-dell-a-sized!" Joey giggles, a fittingly tasteless end for the first four-minute song in their catalog.

The record's charm lies in its sonic consistency. While it didn't outpace hardcore, Johnny got his wish for a harder sound, and Joey and Dee Dee's pop sensibilities -- to say nothing of the assistance provided by Walter Lure on second guitar -- kept things from turning into a Dokken record. Dee Dee's "Outsider" is the LP's token all-timer, giving Joey a bone-deep melody to drill into. Joey's timbre is a marvel of grain and grit, and Dee Dee handles the bridge ("All messed up, hey everyone/I've already had all my fun/More troubles are gonna come/I've already had all my fun") with aplomb and a little bit of twang. The boys did their best to look tuff for the album cover, glowering on a graffiti'd-up subway car. Poor Marky peers from a window, banished from everyone else. Joey got to be a Ramone and an alcoholic; Marky lost one designation after this record, and (wonderfully) ditched the second in time. When it came time to film the requisite music videos, Richie Ramone was there to man the kit.

¡Adios Amigos! (1995)

The dinosaurs are Johnny and Joey, right? The repeated claim that the Ramones never enlarged their sound is dubious. As the years passed, their ballads more closely resembled their inspirations; Johnny's quest for a tougher sound resulted in a clutch of hardcore tracks and a distinct sleaze-rock flavor. Still, they remained four-chord weirdos at heart, content to punch out failed hit after failed hit. And, thankfully, they got to exit on their terms: a mid-tier touring juggernaut, bringing the heat every time. Their stint on Lollapalooza's main stage even provided a bit of closure: Eddie Vedder, Kim Thayil, James Hetfield, Billy Corgan -- truly, the Lou Reeds of their time -- paid mad tribute; the crowds, primed by a previous "farewell" tour, sent the boys off in style. Plus, Johnny finally banked his million bucks. Outside of a cameo on Pearl Jam's live rendition of "The KKK Took My Baby Away," he became a retiree with no need to wield his tools. The Ramones hit the last stop with their cred intact. They didn't notch the traditional markers of success -- the hits, the sold-out American arenas -- but their influence was insidious.

The last Ramones song to chart was, neither fittingly nor ironically, a cover. Introduced with the traditional bassist's count-in, their take on Tom Waits's "I Don't Want To Grow Up" is a surefooted romp with nary a fill from Marky. Like most rockers, the Ramones got to stay kids; thanks to Joey, though, they beamed innocence, not noxiousness. They could have really pushed the point with the second track, Dee Dee's "Making Monsters For My Friends," but C.J. got the chance to yelp away. Largely, the Ramones approach ¡Adios Amigos! as a final curtain, not the sideshow door. "I've done all that I can do," Joey sings on "It's Not For Me To Know," "I don't have any illusions any more." "Life's a Gas" is one final teary tribute to the Ronettes; it crushes with just 13 words. The C.J.-written, Joey-sung "I Got A Lot To Say" cracks mordantly wise with just nine. "Cretin Family" has a piss-off text, but ultimately, it's the band honoring itself, even if C.J. works in a bunch of "oi"s.

Out of all of these worthy candidates, "I Don't Want To Grow Up" (childlike, determined, negating) would've been the perfect closer, but the Ramones had one final trick up their sleeve: Dee Dee himself. Make that two tricks: "Born To Die In Berlin" features the original bassist singing a verse in German. Mixing baroque imagery ("Intoxicated by the orchids/ Abandoned in the garden") with unnerving confession ("I sprinkled cocaine on the floor/When no one was watching"), it's a fine summation of the man's gifts, even if it forgets that there once was joy. Joey takes the chorus, repeats the final line, the riff repeats in classic Ramones fashion, and everything stops.

The Ramones' singular career was over. There would be no reunion shows. The original four, plus C.J. and Marky, turned up at a Virgin Megastore in 1999 to autograph copies of Rhino's Hey Ho Let's Go anthology; Dee Dee spent a good deal of the event grousing about having to cab it, and Johnny nearly clocked him. Two years later, I walked into a mall in Bryan, Texas to buy a Ramones shirt. Back then, I was built like Joey, just a little shorter; I bought a small, and it held up against my frame for a couple years. Joey died the spring prior, having finally released that solo record. Dee Dee was next, overdosing in his Hollywood apartment. Thirteen months later and two miles away, Johnny was interred, dead from prostate cancer. Tommy followed last July: the first and last original Ramone. They had winnowed rock 'n' roll to its ultimate truths, sowing their skewed sincerity around the world, building a legacy of heart and humor nearly unmatched in popular music. There may never be another Ramones, but the lineage will never conclude.

Brain Drain (1989)

It's unclear whether the Ramones were aware of the departed-talent implication inherent in their album's title. Marky Ramone was back, after all, replacing Richie, who was fed up with his bandmates' refusing to grant him respect and, more importantly, a better cut of the profits. At the same time, Dee Dee was on his way out. Though he swore fealty to the band in interviews, he'd experienced an artistic epiphany during a 1987 hospital stay. He adopted his best approximation of a hip-hop nickname -- Dee Dee King -- and sound, recording the "Funky Man" single. Over palm muting and ominous synth buzz, the mainlining MC big-ups his punk credentials and thanks God for his blonde wife. It sounds a little like a serrated version of Inner Circle, and a lot like a Malcolm McLaren wet dream. The first original Ramone to undertake a solo project, Dee Dee's Standing In The Spotlight came out around the same time as Brain Drain. In a 1990 Rolling Stone piece, Chuck Eddy chided the Ramones for slagging off the kids today, rather than "learning from Bon Jovi or New Kids On The Block, the way they once learned from the Ohio Express and the Trashmen." In a weird way, Dee Dee's po-faced flow, as corny as it was, was more in step with the times than his compatriots would ever be.

The '80s Ramones formula holds: a decent rocker to start the first side, a pop tune for the second. If you can tune out the constant cymbal hiss, there's something really vital about "I Believe In Miracles," with its hard-won optimism and taut solo from Daniel Rey. "Pet Sematary," commissioned by Stephen King for the film adaptation of his book, is a kind of song out of time, a sparkling pop-rock number with a glumly resigned vocal from Joey. Sonically, it might as well have come out five years before; nevertheless, it became their highest-charting Modern Rock single (#4). Another would-be hit, "Merry Christmas (I Don't Wanna Fight Tonight)," closes the set. Released as a B-side in 1987, it filled out VH1 holiday playlists for years thanks to a mean-spirited video intro that padded the record's two-minute runtime. Yet another Spector homage, it's a lyrical hash sung bashfully by Joey, who wrote it. It's no "Oi To The World," but it is one more Ramones nugget that contributed to their long-tail life.

A late-period Ramones album carries the feeling of timeshift. In one respect, they ran ahead: having run out of walls to pose in front of, the band commissioned a sweet Giger-meets-Munch painting from Matt Mahurin. Once the listener got past the proto-grunge artwork, though, she was confronted with the same old gang, content to be out of touch. "Punishment Fits The Crime," Dee Dee's only lead vocal, is a psych-punk meditation on prison. Prescriptive and inscrutable, it comes off as third-rate Rush. Corn's aplenty, from "Don't Bust My Chops" (who even says that?!) to "Learn To Listen" (a moralizing anti-drug hardcore number that took four guys to write) to "Come Back, Baby," which sees the return of Vocally Shot Joey, seesawing uneasily from lean punk rock to sunshine pop. The band even resurrected their practice of covering the oldies, refitting Freddy Cannon's nightmarish "Palisades Park" as a creaky wooden coaster, in which Joey's girl almost vomits and they end up moshing near the hot dog stand. Finally tired of the ride, Dee Dee quit the band. Having lost the heart of the band -- and, arguably, their best songwriter -- this could have been the end. But Johnny wanted to bank a million bucks for retirement, and days after Dee Dee's departure, he commenced a search for the Ramones' next bass player, a search that would end up giving the band one final lease on life.

Too Tough To Die (1984)

Yet another attempt to recapture past glory as a punk-rock powerhouse. Look, the Ramones' greatest trait was their stubbornness. Holding out for a hit kept them going at least as much as the dependable income from schlepping the same 15 classics from town to town. Rather than rely on the same supporting cast, they could've demanded a winning vision for a music video, or a marketing department that would know how to present them to a larger audience. But they wouldn't; they had faith in their songs. (That never stopped them from griping, of course.) So it doesn't matter if Johnny wanted to return to Russia, which for him meant a clutch of hard-rockin' goon-tunes. The melodies would always poke through the grime.

The biggest melody belonged to Dee Dee's "Howling At The Moon (Sha-La-La)," an impressionistic take on the drug trade. Eurythmics' Dave Stewart manned the keys, providing the hallucinogenic programming at the start and the spinet-style baroque accompaniment on the bridge. Joey claims full vocal territory: barks here, coos there, tenderness and rage at intervals. A music video was commissioned, an artsy, comic thing that kept the Ramones in a crate, delivered by a gangster Robin Hood to an elderly woman and her lapdog. It supported one of the eighties' best rock singles, and it went nowhere. On the record, it was bracketed by two other songs that exceeded four minutes, a Ramones first. Each song featured a different keyboardist. Jerry Harrison boosts the posi vibes of the double-throwback "Chasing The Night" (Richie does an oompah impression of Tommy, Joey bats around the word "night" like a true doo-wopper), and Benmont Tench of the other Heartbreakers is pretty much invisible on "Daytime Dilemma (Dangers Of Love)."

The point was aggression, and to that end the band brought back Tommy Ramone and Ed Stasium. They frontloaded the record with the harder stuff, leading off with the taunting "Mama's Boy." A rare Johnny/Dee Dee/Tommy co-write, it's a hard rock/psychobilly meld with Joey at his lowest register -- too low, in fact, for the couplet "everyone's a secret nerd/everyone's a closet lame" to become an underground motto. Johnny gets a whopping four songwriting credits on the first half. One's a 55-second instrumental ("Durango 95"); another is "Wart Hog," a Dee Dee showcase and legit hardcore track that became a live fixture. One wonders what a solo Dee Dee would've sounded like as a hXc elder statesman, rather than the joke MC he dressed up as for a time. In his hands, the "wart hog/war!" refrain becomes pure sound, a bileful and joyous thing. (He still ends up railing about "junkies and fags"; whether he's being sardonic or just baiting is immaterial.) Joey gets the next hardcore cut, "Danger Zone," wherein he largely abandons melody for a monosyllabic assault. Still, with "New York City is a real cool town/Society really brings me down," it boasts the worst opening of any Ramones song ever. After so much time away, it was clear that Tommy was brought back for the sound, not the vision. The boys figured they had that covered -- every song was written by a Ramone, even though they had a gutter-punk version of "Street Fighting Man" in the can and a Richie song on the album.

Ultimately, Too Tough To Die is a typical post-Tommy effort: everything is tried, but commercially, nothing stuck. There's rock 'n' roll, rockabilly, synthrock, hardcore -- even a fantastically crusty "Endless Vacation," written and sung by Dee Dee. Thematically, the band foreswore romance, which is a kind of progression; in its place were paisley political sentiment and harrowing survivors' tales. Not that either was insincere: Joey was a frequent activist, turning up on Little Steven Van Zandt's protest jam "Sun City" the year after Too Tough; the year before, Johnny fractured his skull in a street fight with another musician. A smart PR team could've put either to work, but it's likely the severely image-conscious Johnny would've squashed both. Too Tough To Die is a fine record, putting all the band's facets on display. As always, though, it wasn't enough.

Animal Boy (1986)

Too Tough To Die's reunion with Tommy Ramone ended up a one-off. He moved on to the next challenge: producing albums by the Replacements and Redd Kross, then settling into life as one-half of a modernist bluegrass act. But hey, no matter: just like Too Tough To Die, Animal Boy slots a startling Joey Ramone vocal into A1 and a killer pop tune into B1. The rest, though, is mostly dire. Maybe it's because there was no punk impresario to impress. Maybe Joey and Dee Dee's respective substance-abuse problems finally caught up with their creativity. The blame can't lie with ex-Plasmatics multi-instrumentalist Jean Beauvoir, who co-wrote SHINee's "Destination" in 2013, proving he's always Had It. Beauvoir demonstrated his worth by co-writing and producing "Bonzo Goes To Bitburg," the band's last great pop original. Typical Ramones, keeping the hardcore songs separate from the anti-Reaganism -- but nothing else from the era, not even "New Aryans," baited their hooks with this much rage. Most other acts would have hamfisted the song -- the syllables overload the meter on the chorus, the lyric is greased with smarm -- but as often happened, Joey's humanism wins out. After a chuggin' intro, Johnny's buried under Richie and a doorbell xylophone and some wrenching "ah na na na"s, but he was probably fine with that. In return for wounding his reactionary cred, they retitled the song "My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down."

Johnny's vision of a lean rock 'n' roll machine, re-attempted on Too Tough, is asserted all over Animal Boy, even though the three best cuts are essentially pop/rock, and one of them is soft as John Waite in a kiddie pool full of marshmallows. That cut is "She Belongs To Me" -- nought to do with Dylan, instead a super-sensitive threat to kick some interloper's ass, sniped over rubbery acoustic guitar, arena drums and Tunnel Of Love synths. "Something To Believe In" could've been a Cars hit minus Johnny's frantic downstrokes: a keyboard-spangled "Bonzo" soundalike, but with Joey turning the aggravation selfward. The synths goose every line; the backing vocals are zirconian and gorgeous. For the video, the Ramones camp seized upon the "take my hand" line, producing a funny -- if tone-deaf -- parody of Hands Across America ("What is Ramones Aid all about? It's about people. People who care. We think the time has come for caring people who care about people to stand up and be counted.") studded with counterculture guests and also Weird Al.

Speaking of tone deafness, "Love Kills" is a sneak contender for the Ramones canon, a Dee Dee-sung rawk'n'roll ode to his old dead acolyte Sid Vicious. Performed with all the concern of a rubbernecker, farting out baldly hypocritical declaratives ("When you're hooked on heroin/Don't you know you'll never win"), it's one of the funniest punk rock songs ever recorded. It's utterly without mercy. That's about it, though: Animal Boy is a testament to the limits of the bassist's gifts. Having ceded his place as a songwriter of equal productivity, Joey's stuck sleepwalking through Dee Dee classics like "Crummy Stuff," "Apeman Hop," and "Animal Boy" (which at least boasts Johnny's strangled, hollow hardcore timbre). It's clear from his contributions that he wasn't getting the shaft, either: "Hair of the Dog" finds him lazily trailing the chords, halfheartedly defending his alcoholism. The hard-rock "Mental Hell" acquits him better, at least on the mournful chorus, but he's stuck behind the distance of vocal processing.

It was up to Richie to bring out the real beast in his singer. Opening cut "Somebody Put Something In My Drink" is a squealing pop-metal number about exactly what you think it is, but also it's about Joey going absolutely batshit. Growling out of a part of the throat heretofore unknown to medical science, he goes Method on the track: stumbling around, pissing on fruity cocktails, yelling at strangers. By the end, the title reads less like an accusation and more like a request. By this point, stories of the Ramones and their crew whizzing in friends' open containers were legend; if this song was supposed to be harrowing… well, it was, but for different reasons. Animal Boy was the last Ramones record to acknowledge a punk rock beyond theirs. For 1987's Halfway To Sanity, they found a producer with no credentials beyond a decent demo and a love of the Ramones; they moved their pre-show pizza to after, so they could save a stop on the way home. Anyone they wanted to meet came to the shows, not the shops.

Pleasant Dreams (1981)

Joey was starting to think that the problem with the Ramones was the Ramones: the collective identity that obscured individual talents. He pushed, successfully, for individual writing credits. For the first time, Ramones fans could see the division of labor: seven songs from Joey, five from Dee Dee, zero from rock 'n' roll's past. Those numbers were fine by Johnny; he wasn't a songwriter so much as an arranger, the man who built scuzzy skylines from his mates' drafts. As much as he yearned to make it, he felt (probably rightly) that their fans expected the Ramones to be fast and filthy. So he pushed for the harder stuff whenever possible, but not having the songs to match made for charged negotiations. Unfortunately, Pleasant Dreams offered a new obstacle in producer Graham Gouldman. Gouldman was at the tail end of his membership in 10cc, the slightly funny, structurally towering pop/rock act, but his real calling card was his years toiling in the Super K mines, writing the same delicious bubblegum track over and over. This would've been fine a couple of albums ago; now, though, Johnny was eager to get the taste of Spector out of his mouth.

The tension is best felt on the first track, "We Want The Airwaves." Johnny lays down precise midtempo power-chord riffage, with a modest turnaround leading into a dramatic 4/4 piano-key plink. It's got the makings of a minor-key hard-rock classic, up until Joey's lyrics, yet another complaint about the state of the radio. A whisper chases with the title phrase with "that's right, that's right"; it's Donovanesque. That the song closes the Airheads soundtrack tells you most of what you need to know. Or check out "Come On Now," with Dee Dee's genial origin story ("I'm just a comic book boy… I was born on a rollercoaster ride") preceded by a protometal passage, complete with Jon Lord-style organ. Despite the guitarist's best efforts, pop-punk wins the day, in varieties that belie the band's formulaic reputation. Marky's sticks clatter like skeletons on the rare Dee Dee/Joey duet "All's Quiet On The Eastern Front" -- Dee Dee's weedy melodicism is a fine counterpoint. "This Business Is Killing Me" employs nagging sixteenths on the piano and echo on the toms, which harks back to Phil Spector's work on End Of The Century. (There's a bit of shared DNA between this and the Who's "Happy Jack.") The bridge dips seamlessly into hard rock; suddenly, the track is spangled with gorgeous backing vocal phrases. The biggest surprise is the unholy Bo Diddley/calypso bounce of "It's Not My Place (In The 9 To 5 World)," but it's the sole bright spot amongst a quarterspeed bridge, Joey's indolent phrasing, and flagrant namechecking (Jack Nicholson, welcome to Ramones Land).

Obviously, the highlight is "The KKK Took My Baby Away," a pulpy, "Last Kiss"-style pop tune loaded with full-band stops, Marky's hissing cymbal triplets, a vintage "hey! ho!" rejoinder, and a major wind-up into the key change. It was as if Joey was daring radio to make this a hit. Alas, only the Benelux region got the single. A close second is Dee Dee's "You Sound Like You're Sick," which juices the BPMs and pings the BGVs from left to right and back again. It's a frantic kiss-off, the result of studio patience and hard-won proficiency. The power-punk "Sitting In My Room" flashes a little arpeggio and soaring backing vocals that would fit snugly in an R.E.M. track. In case that wasn't enough -- and clearly, it wasn't -- Joey angles for a little corporate cash. "7-11" is an ode to the band's favorite tour stop, a Shadow Morton homage where the guitars go pizzicato, the keyboard sounds like strings, and Joey does the full Mary Weiss on a spoken bridge. The drum sound is starting to reflect its age, a process that would be hastened on Subterranean Jungle. Gouldman became the latest producer to fail at bringing the Ramones pop success. But neither did he give them a pop makeover; he dropped in keyboard and vocal touches, but mostly got out of the way of a cracking set of minor-key brooding and hectic posturing. Still, this latest failure made it Johnny's turn to rewrite the band's history; he decided the band's sound was built on guitar crunch, and did his best to maneuver everyone that way.

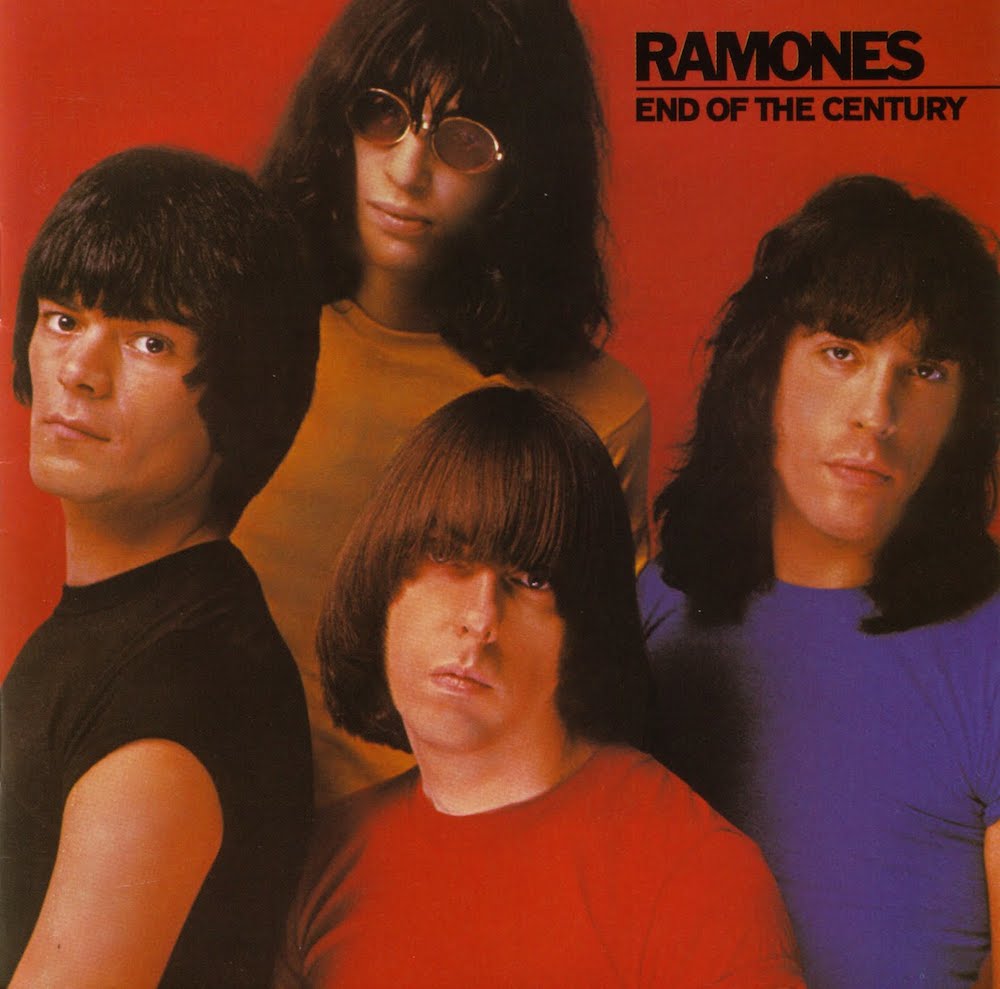

End Of The Century (1980)

During one of the band's L.A. run-ins with Phil Spector, he asked the boys, "Do you guys want to make a good record, or a great one?" The question ought to have disqualified Spector; eventually, though, the Ramones granted the premise. They knew how good their output had been, but they would go to their graves believing greatness dovetails with sales. Yet Spector was an odd choice. Symbolically, perhaps, he was ideal; still, the man hadn't produced a rock 'n' roll record since... well, Rock 'N' Roll, John Lennon's legal-obligation record, released in '75. Mike Chapman (whose work in the UK glitter scene suffused the boys' early glam leanings) was in the midst of a run with Blondie that produced eight Top 40 singles and three Top 20 albums. As Stiff Records' house producer, Nick Lowe helped maintain punk rock's viability in Britain, helming everything from the Damned to Wreckless Eric; after the Basher split with Stiff, Elvis Costello retained his services for four more Top 10 releases. If they'd wanted someone with Sixties cred, there was a wild card: ex-Stones/Traffic/Spencer Davis Group producer Jimmy Miller, who produced Overkill and Bomber for Motorhead, but by most reports, Miller was too smacked-out to do a whole lot.

Spector, on the other hand, was a living legend, the most famous pop producer in history. He was a kid from the Bronx, a tough-talking gun toter who spent his teenage years making hits instead of breaking into laundromats. Johnny saw Spector's hiring as a power move from Joey (reportedly, the producer kept calling the band "Joey and the Ramones"), but he was starved for a hit, so Spector it was. The End Of The Century sessions were famously fraught, completely in line with Spector's goonish, vampiric process, but completely opposed to the Ramones' track-quick/save-money ethos. Johnny, in particular, had a hard time of it. He chafed at replaying the same intros over and over. Dee Dee and Joey forced him to shed his leather jacket for the cover, a sort of pinup for psychopaths. (Johnny looks the roughest, his perpetually dour mug perched at a cubist angle on his neck. He settled for a jackets-on photo inside the record.) Worst of all, a few days into the process, his father died and he departed for New York. It wasn't all rock 'n' roll hell, though: soon after he returned, he began dating Linda Daniele, his future wife -- and Joey's ex.

Yet, against daunting odds, the Ramones emerged with a decent record, one that mostly retained their essence. By all accounts, Spector was sincere in his love of the Ramones. He saw them as the latest link in a chain he helped forge, and thought particularly highly of Joey, whose good/bad/not evil vocal style was its own kind of throwback. The Ramones had been declared art-rockers from the jump -- and a few years later would try to align themselves with the hardcore crowd -- but End Of The Century demonstrated their rock 'n' roll bonafides. Opener "Do You Remember Rock 'N' Roll Radio?" made it explicit, with a fake announcer hyping the band like no pop station ever had. "Do You Remember" succeeds because it's so desperate to ingratiate, riding in on a Bay City Rollers drumbeat, chugging along with a zippy sax section (100% George Harrison, 0% James Chance) and roller-rink organ. "Rock 'N' Roll High School" rides the Beach Boys to semi-immortality; the song is high-energy nonsense, but something like 72% of the words in the song are "rock," and even though it sounds like punky ELO, it endures.

Not all the history is distant, though. A couple of Ramones classics get second chances: "The Return Of Jackie And Judy" finds our heroines at a Ramones show before getting dismissed in a gloomily modulated bridge. "This Ain't Havana" cops the same central rhyme as Dee Dee's "Havana Affair," but instead of an espionage goof, it's a mean little putdown of a welfare recipient. "Havana Affair" featured massive echo on the tom; "This Ain't Havana" ups the stakes with a perpetually detonating drumkit. Spector even helmed their very own "Beth": the twinkling, innocent road-band lament "Danny Says," which takes nearly a full minute to segue from acoustic to electric guitar. It also features their first great bridge (which, again, indulges a little bit of revisionism with the line "listening to 'Sheena' on the radio"). If "Do You Remember" might have struck diehards as gauche, and "Danny Says" as borderline treacly, "Baby, I Love You" was absolutely treasonous. A cover of the Ronettes' evergreen, it features one Ramone: Joey, who milks the lovesickness for everything it's worth. Instead of castanets, there's the god Jim Keltner on drums and clopping percussion like a medium-size time bomb. The single went to #8 in Britain, a more hospitable clime for adorable fluff.

Johnny's on record declaring that the slower songs benefitted from Spector's hand much more than the uptempo ones. But the punkier numbers have bite, and a lot of that is due to Spector. "I Can't Make It On Time" would be a Ronettes tribute even without the twinkling organ on the chorus: Joey's working a cracking, vulnerable melody, fashioning the phrase "on time" into a snug existential prison. The standard handclaps are fanned out until they sound like hedge clippers. "I'm Affected" -- led in by a sterling Dee Dee bassline -- veers close to the spirit of NWOBHM, helped along by massive echo on the toms and a divebombing twin-guitar attack. Speaking of Dee Dee, his "Chinese Rock" makes its Ramones debut here. Johnny originally nixed the song, so Dee Dee gave it to friend and fellow junkie Johnny Thunders. The Ramones' take doesn't carry the same strung-out verisimilitude, but it ups the tempo and boosts the drum gallop on the refrain. (Oddly, the Ramones did without the count-in -- their bassist's trademark -- and changed a lyrical mention of Dee Dee to "Arty," as in Arturo Vega.) Spector's work on "All t

The Way" is worthy of Tommy's production on albums two through four, with metallic guitar stings, Marky's frantic pace, and angelic blocks of harmony vocals. "Doomsday's coming - 1981," Joey warns. (1981 is, of course, when Reagan assumed the presidency, but alas, the song was recorded before Ronnie threw his hat in the ring.)

But if their sense of history was skewed, why not their sense of eschatology? "It's the end, the end of the seventies/It's the end, the end of the century," goes the key couplet on "Do You Remember Rock 'N' Roll Radio?" That's a great rhyme, but it's also a glimpse into the limits of the band's imagination. British radio was alive with the sounds of unrest and fuckaround goofiness; American radio settled for the sonically neutered (but thematically compelling) New Wave -- a term Seymour Stein desperately tried to glom onto for the Ramones' use. End Of The Century took a couple of weeks to record and months to mix; it limped into stores in February of 1980. From start to finish, the album took almost as much time as elapsed between the release of Ramones and Leave Home. Though no singles landed, the LP nearly cracked the Top 40, and that was enough confirmation for Warner Bros. that the boys should stick to a poppier sound. The band was without Tommy, their well of compositions was nearly tapped, and they embarked on another tour with Joey and Johnny in a detente that would last the rest of their career. Meanwhile, American punk was only getting louder.

Road To Ruin (1978)

Now generally regarded as the last classic Ramones record, Road To Ruin saw Marky Ramone tap in so Tommy Ramone could live something like a regular life. Tommy stuck around though, long enough to produce the record with Ed Stasium. Road To Ruin is also the last time the band tried to crack the national consciousness with their original sonic blueprint. That's not to say this is some punk-rock last stand; in fact, this record is the closest the Ramones' sound came to reflecting the era. "Don't Come Close" is Raspberries-flavored power pop, loaded with chiming guitars that Johnny never touched. Same for "Questioningly," a sweet picture of romantic disconnect swept off KISS' cutting-room floor. Even the obligatory cover (the Searchers' "Needles And Pins"), is balefully faithful, girded with acoustic guitar and spangled with tambourine.

But all that sweetness is leavened with some of the band's grouchiest compositions. "I Just Want To Have Something To Do" riffs on a line from the debut, but it plays like the show opener in purgatory's arena, all metal twiddles and petulant chordage. "I'm Against It" is straight comedy, a list song that sees Joey voting no on everything from communists to summer to circus geeks. "Bad Brain" is basically the same song with a kickass rhyme scheme and a bridge that showcases the band at its most polyrhythmic -- which is to say, not very. (It's also noteworthy for inspiring the name of one of hardcore punk's biggest acts. That's right… the Crucifucks.) And, of course, there's "I Wanna Be Sedated," bedecked in Marky's bellwork and featuring some of Johnny's finest tightassed hacking. It wouldn't become a hit until alternative radio became a thing, but it's the premier rock-star song.

And at this point, the Ramones were rock stars, at least as a touring concern. They gigged all over the States and Europe in '78; at one point, their opening act featured Daniel Rey, the man who would soon become a vital collaborator. Marky Ramone, a Brooklyn boy with Wayne County And The Heartbreakers on his resume, was no mastermind, but he had the pedigree, gradually loosening Tommy's restrictions on fills while preserving the feel. But bigger vistas still called, and when the Ramones got the opportunity to record for an old idol, they took it.

Leave Home (1977)

They already had the songs. Having logged about 150 live shows, give or take, the Ramones had the facility, too. Sire tossed them four thousand more bucks and the services of Tony Bongiovi, a veteran engineering/production hand who'd recently finished tracking Talking Heads' debut. (Three years later, Tony give his cousin, John Bongiovi, his first break, getting him on Meco Monardo's Christmas In The Stars: Star Wars Christmas Album.) The Ramones still had a backlog of tunes, and the combination of more time and better production made for a muscular set. They abandoned their stereo-separation gimmick and got Johnny a bigger chainsaw. Joey's vocals are still multi-tracked, but it's less obtrusive, and he's going further into his lower register. As you'd expect, Dee Dee's bass takes a step backwards in the mix, but I'm not sure even he would complain.

Setting the production aside, the biggest leap on Leave Home is the nagging riff cycles that stand in for solos… on the debut, they were fidgety placeholders, the artiest thing in the band's arsenal. Now, the boosted levels more than cover the lack of lead guitar. They're additive. The legend holds that the Ramones wrote 30 songs, and 29 of them ended up -- roughly in the order they were written -- on the first two records. But while I'm pretty sure that's not how bands work, the first three LPs are near-matches in songcraft and theme. For the devoted listener, "Carbona Not Glue" was a cute follow-up, both in subject matter and in the way it repeated verses with a shrug. To Sire, it represented a potential legal headache, and the song was swapped out. The Nazi shit from "Today Your Love..." gets a similarly jokey update on "Commando"; the new rules include following "the laws of Germany" and eating "kosher salamis." The lancing "Glad To See You Go" starts with the promising line "gonna take a chance on her," but quickly goes off the rails, referencing gun murder and Charlie Manson. Didn't these guys want to hit the big time? The first single was "Swallow My Pride," an oblique gripe against an industry that hadn't made them Grand Funk Railroad-large after two years. (To be fair, Joey does sing the title as a series of gulps.) The second was "I Remember You," which doubles down on the frustration while halving the words.

But whether they knew it or not, Leave Home did kick open the gate. They were never going to be Grand Funk, but songs like the cheery/crushing "Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment" and the immortal "Pinhead" made clear who belonged to the first wave of Ramones fandom. Just by existing, Leave Home freed the debut from being a weird, one-time document; by boosting the levels and sticking to the script, it drove thousands of weirdos into madness. They'd locked in their iconography: Vega's Great Seal parody (the busiest punk-rock logo in history), the HEY HO/GABBA GABBA signs, Vega (or a drum tech) dashing across the stage in a Zippy mask. They could've toured off the first two records until the end of time. Thankfully, they didn't have to.

Rocket To Russia (1977)

Like a shitty MP3, time distorts by compression. The disposable, timeless pop that permeated the Ramones' songwriting ruled the airwaves just a decade before they formed a band. And the year after Rocket To Russia, a Santa Ana outfit named Middle Class put out the Out Of Vogue EP; the tempos that had stunned Bowery crowds were nitro-boosted, resulting in an omnidirectional thrash that couldn't be sustained for much more than sixty seconds. The hardcore scene shared the Ramones' thirst for playing anywhere, but Black Flag and Hüsker Dü didn't settle for a BTO opening slot. While punk outfits from Boston to Long Beach were scavenging the country for every handful of true believers, the Ramones kept chasing hits.

The closest the Ramones came to a hit was here, with "Rockaway Beach" b/w "Babysitter." The B-side, a lovely little tale of the bluest balls, was a last-minute replacement for "Carbona Not Glue" on the UK version of Leave Home. The A-side is fucking "Rockaway Beach," surf rock nirvana with the twang banned, introduced by Dee Dee's immortal count-in and an all-time opening line ("chewin' out a rhythm on my bubble gum"). It was painfully clear by now that the Ramones were good for a half-dozen punk-pop gems like "Rockaway Beach" on every LP, and that every single one of them was doomed. And this one had all the hits, both original ("Cretin Hop," "Teenage Lobotomy," "We're A Happy Family," "Ramona") and secondhand ("Do You Wanna Dance, "Surfin' Bird"). With "Here Today, Gone Tomorrow," there were even the signs of sophistication: the ghost of a solo poking through a downcast strummer. Joey's second vocal keeps slipping loose, a bummer echo; the topline doesn't resolve, it dissolves. "I Don't Care" predicts Danzig while channeling Iggy; Dee Dee's plaintive "he don't care" is beamed in from Planet Shangri-La.

With Rocket To Russia, the recording budget climbed to five figures. The investment was calculated; Warner Bros. took control of Sire's distribution in '77, and before recording, a cross-continental tour re-pollinated the West Coast and Great Britain. The Ramones replenished their store of hits, releasing their third classic in an insane 21 months. They could do funny, urgent, nihilistic, lovelorn. They wrote a little comic-book world and liberally drew themselves into it. They had the image and the urge to succeed. When they didn't, they pointed fingers inward and out: running through eight producers on the next seven albums, blaming the Sex Pistols' antics for tarnishing punk rock in the public's eyes. Of course, the Ramones were a genre unto themselves, but when it came time to record Road To Ruin, they worked the edges, toughening up Johnny's timbre while introducing elements of country-rock and power pop. I'd like to think that there was some night in November -- perhaps in a Manchester hotel room, possibly in a van heading to Pittsburgh -- when Tommy, Dee Dee, Joey and Johnny cracked some beers and toasted their accomplishments. They had become world-beaters in all but name.

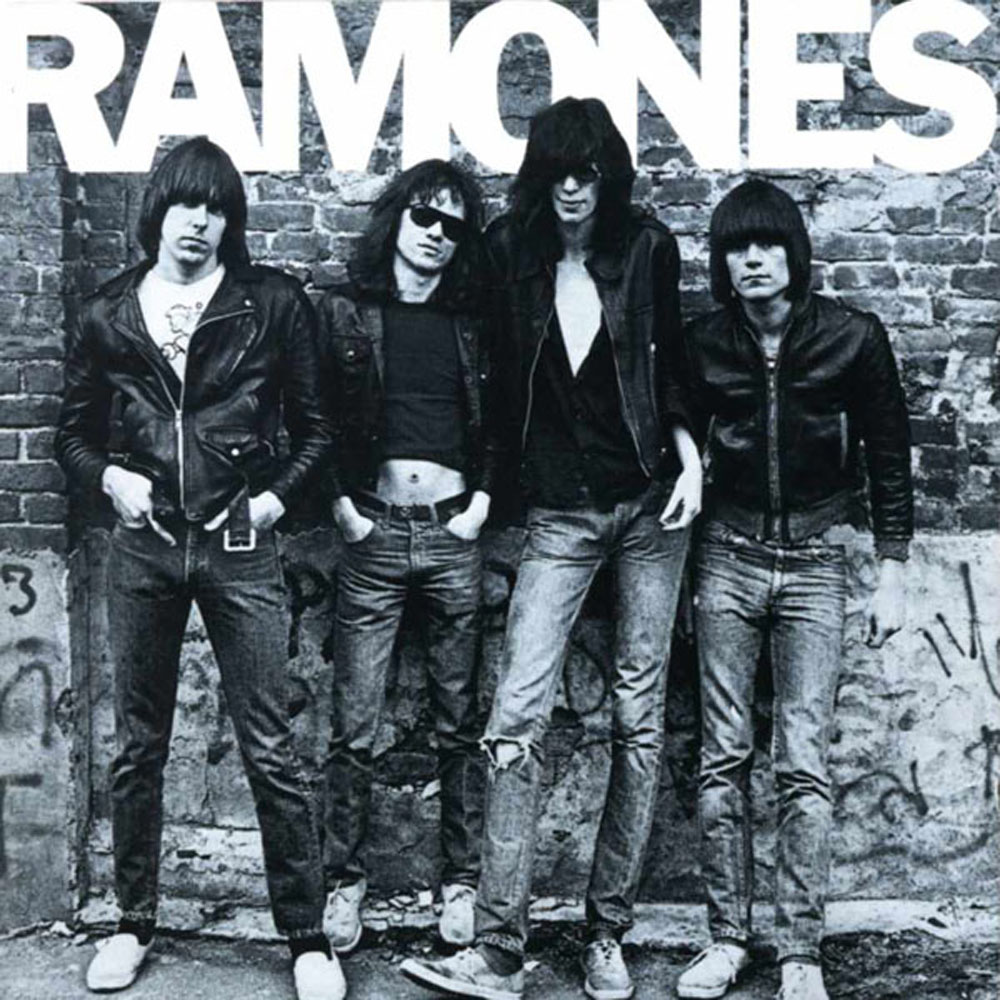

Ramones (1976)

I get that sticking this up top implies the band fell down a hill. I acknowledge that due to beefed-up production, records two through four were the true springboard for punk rock. I concede that the Ramones knew this, and whenever they attempted to reclaim older territory, they weren't harking back to this peculiar mix job. But those caveats make Ramones a singular document. The separation -- Dee Dee in the left channel, Johnny in the right, patterned after the Beatles without a second thought -- keeps each Ramone at equal power. Tommy is so intent on sturdiness, his highwire deliberation produces melodies by itself. Dee Dee's nubby bass tone contributes more to the album's insistence than anything else. (He carries large sections of "Beat On The Brat.") Johnny's rhythm style drips impatience: it's too modulated for rage, too focused for abandon. And Joey caps it all, gargling syllables, pulling all kinds of faces: he's making a record, and he's having a blast.

Ramones cleared nothing up for the arthounds who'd seen the boys' CBGB residency. Some were convinced that the Ramones were making an arch statement, a reification of rock 'n' roll insanity; these people usually considered themselves art rockers. Others believed that the Ramones were brain-damaged suburbanites, brutes with a schlock fixation; these people can be found in the pages of Please Kill Me obsessing, twenty years later, about who took more drugs. Still others just thought the whole deal was funny as hell. When Ramones dropped, everyone found something for his or her side. The pace was Herb Washington fast, the tone whipping from insurrectionist to lovestruck to goony. And throughout, there's a remarkably consistent sonic approach, thanks to a breakneck recording schedule and Craig Leon on the sliders (with assistance from Tommy). The record conjured fevers and obsessions: a Back From The Grave box set on one platter. Saws are revved, drums detonated; a massive pipe organ was shrunk to Ramones size and deployed on a cover of Chris Montez's manic "Let's Dance."

Dumb luck had nothing to do with Ramones, which is essentially a perfect record. Intent on Making It, the band wrote a batch of tunes and gigged them relentlessly; when it came time to record, they were automatic. And when it came to the moment, they delivered. "Blitzkrieg Bop" gives the game away in the title. The chant was a nod to the Bay City Rollers -- at one point, they were the competition -- but it's delivered in hiccups. Johnny strangles his way through the changes; Tommy strikes up an oompah beat. Is it about a dance? A riot? Not even the band knows. Even their supporters thought they were one-track creeps, despite songs like "53rd & 3rd" (a first-person account of a Vietnam vet turning tricks, capped by a Dee Dee-sung bridge that might be recorded music's worst vocal to that point) or "I Don't Wanna Go Down To The Basement" (an obsessive little sketch that reveals everything by leaving so much unsaid). "Today Your Love, Tomorrow the World" starts as a doom-punk document, then rips itself apart to reveal the most posi of hearts. Seymour Stein was the head of the label, and, like Joey, Jewish. He could've quashed Dee Dee's Nazi imagery, but kept faith in his act. The singer repaid him by hollering those Reich rhymes with insouciance, an evisceration of shock before the triumphant album-ending refrain.

Stein also likely realized that an album like Ramones wouldn't be big enough to attract controversy. They had so much to say, but their musical vocabulary was only so big. So the record has about 10 alternate-universe hits, scuttled by subject matter or tempo or the vocals. Of course, this sort of situation is catnip to critics. One contemporary publication declared the Ramones were possibly the greatest singles band since the Velvets; they were either sardonic or out of their minds. Today, AcclaimedMusic.net pegs the debut -- which, again, was recorded in a week and spawned no hits -- as the 38th-most lauded record ever. Of the records that placed higher, only eight are debuts: The Velvet Underground & Nico, Never Mind The Bollocks, Are You Experienced?, Horses, Marquee Moon, The Doors, Funeral, Blue Lines. The Doors aside, pretty good company. When Erdélyi Tamás looked at three high-school classmates, he saw greatness; even better, he nurtured that greatness behind the kit and the boards. When he turned in his leather jacket, the rest of the Ramones were no less committed to their goals than they were on this gamechanging record.